By Robert Reed

By Robert Reed

If you love me

as I love you,

Then you will be

my sweetheart true.

– verse from fancy,

heart-shaped 19th century

Valentine.

Giving valentines to those dear to us has been a practice for centuries but it was the Victorians that made them so wonderfully fancy.

During the 17th century both men and women devoted hours of handiwork to preparing Valentine’s Day messages of love. Images were hand-drawn or painted in water colors, carefully cut out, and pasted together often with bits of thread, lace, and silk.

During the 17th century both men and women devoted hours of handiwork to preparing Valentine’s Day messages of love. Images were hand-drawn or painted in water colors, carefully cut out, and pasted together often with bits of thread, lace, and silk. Historians say the practice of sending attractive artwork valentines was popular first in England during the early 1700s and had become established in America by the 1740s.

A valentine composed of a series of hand-drawn puzzle images attached to a single sheet of paper, about six by eight inches in size was one displayed by a major east coast museum. It was signed T. Bailey and made around 1788.

By the 1790s pictorial writing paper was available to further embellish homemade valentines and frequently symbols of flowers, birds, or hearts were added as decorations as well. Plus, of course, a tender message or verse.

At the dawn of the 19th century the movement for valentine messages was toward even finer examples of decoration. Scissors and pin pricks imitated delicate lace, and even crewelwork and embroidery were added by the ambitious admirer.

The Dobbs Company of England was providing fancy paper for such devoted uses as early as 1803. Eventually the company evolved into the commercial manufacture of valentines under such names as H. Dobbs and Company, Dobbs, Baily and Company, and later Dobbs, Kidd and Company.

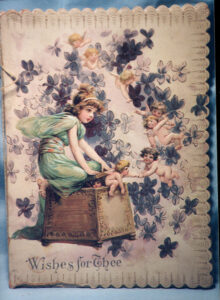

Dobbs’ valentines put heavy emphasis on flowers and cupids along with pressed silk and satin backings. Most were further enhanced with skillful hand painting. By the late 1830s firms in London were able to simulate lace from paper with hand operated presses and the layered lace look became available to the masses.

Dobbs’ valentines put heavy emphasis on flowers and cupids along with pressed silk and satin backings. Most were further enhanced with skillful hand painting. By the late 1830s firms in London were able to simulate lace from paper with hand operated presses and the layered lace look became available to the masses. Widespread use of commercial valentines, for all of their striking appearance, did not develop in the United States until the beginning of the machine age in the 1840s. Meanwhile envelopes, although twice as expensive to mail, gradually became available and in some cases could be almost as elaborate as the valentines.

Clearly it was an era when “the most popular token of love was the valentine,” according to Robert Etter the author of the book Tokens of Love. “Those fragile paper and satin concoctions surrounded by clouds of lace could make each postal delivery a crisis. “

Appearing on the horizon in the latter 1840s were a number of American commercial firms which produced fancy valentines. Among them were Turner & Fisher of Philadelphia, Charles Mangus, Elton and Company, and T. W. Strong all of New York City. In later years they would be joined by P.J. Cozzens, the McLoughlin Brothers, J. Wrigley and more.

In 1848, Strong published the following newspaper advertisement:

“Valentines! Valentines! All varieties of Valentines, imported and domestic, humorous, witty, comic… in the most superb manner, without regard to expense. Also envelopes and Valentine Writers, and everything connected with Valentines, to suit all customers, prices varying form six cents to ten dollars; for sale wholesale and retail at Thomas W. Strong’s…”

Shortly afterwards Esther Howland of Worcester, Massachusetts launched her own fancy valentine firm after being duly impressed with elaborate examples from England. Miss Howland used her own artistic skills but imported much of the lace paper from the British.

Shortly afterwards Esther Howland of Worcester, Massachusetts launched her own fancy valentine firm after being duly impressed with elaborate examples from England. Miss Howland used her own artistic skills but imported much of the lace paper from the British. But the 1850s Howland had established a major operation in New England. She employed family, friends, and others to produce delightful valentines of paper lace with gilted backing and other creative touches. In later years Howland cards were stamped on the back with a red letter H or a white heart with a letter H centered in it. By the 1870s Howland had formed the prosperous New England Valentine Company and many cards were then marked accordingly. N.E.V. Co.

In the 1880s Howland sold her business to George C. Whitney, a former employee who had for many years manufactured similar valentines.

Elsewhere those who created valentines usually felt more was better. Besides lace and glimmering paper Victorians gushing with ingenuity were known to add ribbons, beads, tinsel, moss, pressed flowers, dried seaweed and assorted combinations to their tokens of love.

Major changes developed for popular valentines during the latter 19th century. For one thing they were big business, and sold in nearly every major store in America. For another they became industrialized, makers like Whitney and others turned to their own machines for die-cutting, embossing, and even paper lace thus nearly ending imports.

Soon however delicate lace was not enough. Louis Prang of Boston began offering beautifully lithographed valentines in color bearing reproductions of fine works of art. Prang, who published all manner of cards, moved valentines forward with color images of flowers, pretty girls and simple messages of love.

By the 1890s the full introduction of color-printing process known as chromolithography had turned the entire printing industry around. Now valentines and other greeting cards could be printed in brilliant and detailed color at a relatively low cost. The era of ‘new’ fancy Victorian valentines was in full bloom.

By the 1890s the full introduction of color-printing process known as chromolithography had turned the entire printing industry around. Now valentines and other greeting cards could be printed in brilliant and detailed color at a relatively low cost. The era of ‘new’ fancy Victorian valentines was in full bloom. Many of the traditional printed valentines continued to delight the public well into the 1900s. Even fancy lace valentines were produced and widely sold during the first decades of the century. The Whitney company continue was still prospering when it was taken over in 1915 by the founder’s son, Warren Whitney. It continued to be a major producer until the wartime paper shortages of the 1940s.

The turn of the century saw a few new twists added to already fancy valentines. Many were made with paper honeycombs which could be unfolded or pulled out for further elegance.

Authors Dan and Pauline Campanelli describe pull outs of the early 1900s as incorporating, “a flat piece of lightweight cardboard, diecut in a delicate, lacy shape and printed in full color, with the lowest portion folded up.”

“As this lowest part is carefully pulled down,” they conclude in Romantic Valentines, “layers of printed diecuts attached to the card by paper hinges separate from one another and appear to stand by themselves.”

All these things abounded in the Victorian era and give history some of its finest and most fancy valentines.

Recommended reading: Romantic Valentines, A Price Guide by Dan and Pauline Campanelli (L-W Book Sales)

Valentines With Values by Katherine Kreider (Schiffer Publishing).

Follow Us