By Henry J. Pratt

By Henry J. Pratt A messenger rode up to the White House on an early November day in 1863, and delivered an invitation to President Abraham Lincoln to assist in dedicating the new national cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

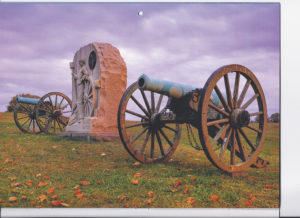

The greatest battle in the Civil War had been fought at Gettysburg for three days the previous July. Dead, wounded and missing totaled more than 50,000 soldiers of some 150,000 Union Army troops who turned back the Confederate Army’s last invasion of the North.

After the battle, about 2,000 of the 6,000 dead were buried in Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery. Lincoln was not slated to be the featured dedication speaker. That honor went to Edward Everett, the most renowned and sought-after U.S. orator of the day.

Instead, the President was to do little more than cut the graveyard ribbon and present a few dedicatory words. The speaking invitation delivered that November day asked Lincoln, “as Chief Executive of the Nation, formally to set apart these grounds to their sacred use, by a few appropriate remarks.”

To the surprise of some, Lincoln accepted. the President had not been a popular speaker, particularly in the East. His voice was high and thin, but even more vexing, he had a habit of lacing his talks with a bit of earthy humor or a rather crude joke.

So the dedication committee delayed inviting Lincoln for as long as possible in the hopes that his schedule would be committed elsewhere. Their delay left Lincoln little more than two weeks to prepare his remarks. When he boarded the special train that would carry him to Gettysburg on Nov. 18, Lincoln clutched only a bare outline of what he would say. But he worked hard during most of the all-day trip North, rewriting and refining his speech.

The dedication ceremony began at noon on Nov. 19 with an invocation by the Chaplain of the House of Representatives. The prayer was followed by Everett’s introduction. After acknowledging the President and other gathered dignitaries, the orator launched into his two-hour address.

Everett traced the nation’s history and the Civil War, as well as gave a recap of the three-day July battle. He denounced states’ rights and secession, comparing the U.S. with ancient Greece and Rome. Everett’s talk was just what the 15,000 spectators expected and wanted. When the silver-tongued orator finished, they applauded long and loud.

Next on the program, the Baltimore Glee Club sang an ode composed specifically for the occasion. Then, Ward Lamon rose and introduced the President. As Lincoln approached the podium, the gray November overcast parted, and a ray of sun bathed him in soft light.

Quietly adjusting his spectacles, Lincoln then proceeded to deliver, in what one reporter called “a sharp, unmusical treble voice,” the brief remarks that the dedication committee had belatedly requested him to make.

“Fourscore and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

Within the next 240 words, Lincoln summed up the meaning of the cemetery ceremony, the battle of Gettysburg, and the war. Few people in the crowd, however, had time to grasp the two-minute message’s eternal theme and eloquent words.

Lincoln’s talk was over so quickly that a photographer setting up his camera to capture the occasion wasn’t ready. His historic photograph shows Lincoln sitting down, his talk over. The address was over so quickly that few people—including Lincoln—realized the full impact of what he’d just said.

The spectators were so confused by the brevity of Lincoln’s remarks that their applause was delayed, then later so scattered and brief as to be barely polite. Lincoln turned to Lamon and discouragingly lamented, “It’s a flat failure, and the people are disappointed.” Indeed, many were.

The Chicago Times soon reported, “The cheek of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly, flat and dishwatery utterances of the man who has to be pointed out to intelligent foreigners as the President of the United States.”

But not all the reviews of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address were so savage and belittling then, and certainly not now, some 155 years later. A Massachusetts newspaper, which printed the full speech text, called the address “deep in feeling, compact in thought and expression, and tasteful and elegant in every word and comma.”

A Cincinnati editor pronounced the speech to be “the right thing in the right place, and perfect in every respect.”

Edward Everett wrote Lincoln a letter the next day. He said, “I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

Lincoln had said in his address, “The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here.” Here, the President was dead wrong. As the decades roll by, Abraham Lincoln’s “silly, flat and dishwatery utterances” are now regarded as one of the greatest speeches in American history, if not the English language.

Follow Us