Remembering the American Revolution, 1776-1890, a recent exhibit at the DAR Museum in Washington, D.C. explored how citizens of the new United States maintained a connection to the Revolution by saving and creating objects.

Remembering the American Revolution, 1776-1890, a recent exhibit at the DAR Museum in Washington, D.C. explored how citizens of the new United States maintained a connection to the Revolution by saving and creating objects.

How do you create a collective memory?

The new nations’ first three generations of citizens shaped our memories of the American Revolution. People saved and created items to commemorate the struggle for independence to keep Revolutionary ideals alive during an era of great change and conflict. These objects form the foundation for our own memories.

These are a few highlights from Remembering the American Revolution 1776-1890:

“Our own are the last eyes that will look on men who looked on Washington; our ears the last that will hear the living voices of those who heard his words. Henceforth the American Revolution will be known…by the silent record alone.”

—EB Hillard, The Last Men of the Revolution

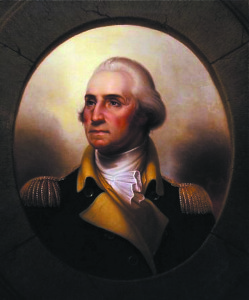

The country mourned the December 1799 death of the illustrious Washington. Though not the first veteran of the Revolution to die, his death was a signal of what was to come throughout the 1800s; eventually those who formed the new nation would not be present to provide guidance. How would the ideals of the Revolution be perpetuated? Who would remember the sacrifices of the founding generation?

George Washington died December 14, 1799, at his home at Mount Vernon, Virginia. Solemn funeral processions took place in every city across the country during the first weeks of 1800. The sad parades were an outpouring of grief and an illustration of national unity. Authors, orators, and publishers offered hundreds of eulogies to the lost Father of the Country.

On a lighter side, the current Museum Exhibition is “An Agreeable Tyrant: Fashion After the Revolution” October 7, 2016 – April 29, 2017

The exhibition displays men’s and women’s clothing from 1780 to 1825 in a dozen period rooms throughout the museum. It considers how Americans fashioned a new identity through costume; on the one hand, Americans sought to be free from Europe, yet they still relied heavily on European manufacturing and materials.

It’s 1781. The Revolution is over, and we are no longer colonists! We are citizens of an independent nation.

But wait—are we going to follow English and French fashions? The royal courts and aristocracy set the fashion. We’re trying to be democratic now! Should we make up our own styles? Should we wear only American-made fabrics, even though they are in short supply? What’s a patriotic American to wear?

Another Exhibit in the DAR Museum explores the “Stately Seats” of the patriots. Pictured is a sofa owned by Thomas McKean, a Delaware signer of the Declaration of Independence, this distinctive sofa was made in Philadelphia between 1770 and 1790.

Sofas were expensive and rare items even among wealthy families of the 18th century. The peaks flanking the back of the sofa’s central arch or serpentine are rare decorative options; in fact, only eight other examples are known to exist. The wool upholstery was fashionable, more durable and less costly than silk. Whatever the fabric, upholstery was an expensive purchase, costing between 10 and 20 pounds—almost as much as a yearly salary for most people. (The upholstery shown here is not original, but the fabric is an accurate re-creation.)

The sofa, listed in McKean’s 1817 estate inventory, was a gift of the Mary Washington Chapter of DAR, Washington, D.C. to the Museum.

Other Stately Seats include this pair of mahogany armchairs ordered by President James Monroe for the East Room of the White House in 1818. The order was placed with Georgetown cabinetmaker William King Jr., and the set originally consisted of 24 chairs and four sofas. The chairs cost $33 each, and the purchase of the set was financed by the “furniture fund” that had been appropriated by Congress in 1817 to refurnish the White House after the British burned it down three years earlier.

Originally supported upon brass casters, the chairs were not upholstered. They were described in the 1825 inventory of furniture in the President’s house as “unfinished.” The chairs were made usable in 1829, when the East Room was decorated by Louis Veron & Co. of Philadelphia. According to an invoice, the set was “stuffed and covered, mahogany work entirely refinished, and cotton covers [supplied].” At that time they were upholstered in “blue damask satin,” and the reference to “cotton covers” suggests that the set was provided with slipcovers used to protect against sunlight and dirt during the summer months.

In 1873, the set was sold at auction when Boston decorator William J. MacPherson redecorated the East Room under President Ulysses S. Grant. The DAR Museum purchased the chairs from an antique store in 1961.

The DAR Museum in Washington, D.C. is truly the one place that the American Revolution and the historical items from succeeding generations have been preserved. It makes it one of the most visited museums in the world. For more information, go to or call the Museum at 1776 D Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20006, (202) 628-1776

Follow Us