By Robert Reed

By Robert Reed The beautiful brooch traditionally had been one of the most enduring types of jewelry as well as one of the most varied.

Women have affixed these large and decorative ornamental pins on their clothing for centuries. Some brooches could be fashioned from cardboard or human hair and be fairly plain, or they could be adorned with gold and diamonds and be nearly priceless.

By the early 19th century the brooch had become a true fashion statement of the rich and famous. Initially only the wealthiest woman could afford the assembly of precious stones and fine metals required for a proper brooch. The more lavish and dazzling the better.

Gradually however the trend of a clever brooch began to extend to a wider variety of social classes and tastes.

“The brooch was probably the most popular and widely produced form of jewelry” in the entire 19th century according to Stephen Giles author of Miller’s Jewelry Antiques Checklist. Accordingly, “examples offered a wide range of styles, materials and levels of quality.”

“The brooch was probably the most popular and widely produced form of jewelry” in the entire 19th century according to Stephen Giles author of Miller’s Jewelry Antiques Checklist. Accordingly, “examples offered a wide range of styles, materials and levels of quality.” Certainly the brooch selection of that historic century was vast.

The turquoise and diamond brooch was popular early in the 19th century, but other choices could be of solid gold with matching earrings, or a mixture of rubies, sapphires, and emeralds.

Ultimately there was a world of other fashionable materials too including cameo, coral, enamel, mosaic, painted porcelain, and pearls. The image of the brooch would vary widely as well extending from a mere cluster of jewels to the specific shape of a bird, flowerpot, Greek cross, butterfly, Egyptian beetle, or eagle. Then too there were widely differing designs of pinwheels, starbursts, loops, bows, and scrolled frames.

By the middle of the 19th century the fashion world was awash with diverging brooches in seemingly endless styles.

In 1861 a leading women’s magazine offered information to readers to “wishing hair made into pins.” The magazine assured a large number of orders had already been recently filled and ladies were delighted with the results. They added, “hair is at one the most delicate and lasting of our materials and survives us like love.'”

At the other end of the brooch ‘rainbow’ might be a bejeweled item with a domed center and an assortment of diamonds, opals and corals. Some middle and latter 19th century brooches were large enough to include equally attractive pendant attachments in the design. In some cases the pendants were removable or could even be converted into smaller brooches themselves.

At the other end of the brooch ‘rainbow’ might be a bejeweled item with a domed center and an assortment of diamonds, opals and corals. Some middle and latter 19th century brooches were large enough to include equally attractive pendant attachments in the design. In some cases the pendants were removable or could even be converted into smaller brooches themselves. At one point the prestigious Johnston and Company at Union Square in New York City offered brooch selections such as the circle of swallows, the diamond bow-knot, the Roman wreath, the Dragon and pearl, and the six-diamond loop. All were advertised in the 1890s as “effective and tasteful ornaments,” and further “all of these may be worn as pendants.”

Smart shops in the center of New York City seemed to do a thriving business in the sale of striking brooches near the end of the 19th century. Prices, at the time, ranged from $15 to $150 depending mostly on the use of diamonds instead of pearls.

Not that the popularity of the brooch needed a boost, but the age of Art Nouveau did indeed push the jewelry item to new heights. The flowing lines and floral forms of the French inspired ‘new art’ were perfect for the brooch.

Indeed the Art Nouveau movement, “had a dramatic effect on the styles and materials used for brooches,” comments author Giles. “Metalwork designs were flowing and vegetal, with graceful intertwined shapes featuring floral and abstract motifs.”

The discreet shopper might find an enameled dragonfly with sapphire body, a diamond-encrusted spider, or a peacock with a body of rubies and pluses of sapphires and garnets. A sprig of flowers could ‘bloom’ with a mixture of gold, pearl, and emerald. A bird of gold and turquoise could brandish eyes made of diamonds.

Much of the Art Nouveau influence came from the work of French glassmaker and jeweler Rene Lalique. Now the lovely brooch was part of a movement toward nontraditional images of not only the dragonfly and spider but the bat and the serpent as well as clover and wildflowers.

Much of the Art Nouveau influence came from the work of French glassmaker and jeweler Rene Lalique. Now the lovely brooch was part of a movement toward nontraditional images of not only the dragonfly and spider but the bat and the serpent as well as clover and wildflowers. Louis Tiffany’s very own Tiffany and Company launched a department of “artistic jewelry” just to keep up with the creative demand.

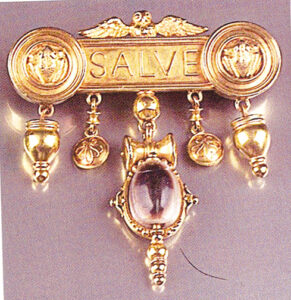

Accordingly there were a multitude of brooch makers from the mighty to the meager. A brooch decorated with owls and frogs could come from Italy’s renowned Ernesto Pierret, or something equally unusual from France’s Giacinto Melillo. Eventually the list of those making eloquent brooches became vast and worldwide from Cartier to Gorham, Marcus and Company, Unger, Vever, and Wiener. Other memorable maker’s marks included Edward Oaks, Reed and Barton, Margaret Rogers, Schlumberger, James Muirhead & Sons, and Watherston & Son of London.

The J.H. Johnston Company offered what they called the Roman Gold brooch during the 1890s and charged extra for a diamond center. The Empire Wreath brooch was also a big item. “The wreath,” noted one firm’s advertisement during that decade, “appealed to seekers after ornamental beauty long before the time of the Emperor. In now using it to ornament our smaller silver articles, we feel that its grace and simplicity gives them a lasting charm.”

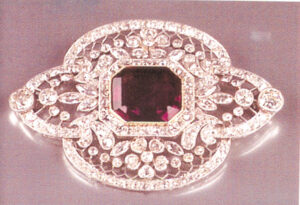

Art Nouveau in worldly style and in brooch design was closely followed by the era of Art Deco. While the Art Deco vogue was largely attributed to the Paris Exposition of 1925, it had actually been fully developed much earlier in the 20 century. The Art Deco brooch stressed geometric figures and symmetrical forms and often made lavish use of brass, chrome and enamel in dazzling combinations.

The Paris event itself featured over 400 jewelry firms worldwide and a vast assembly of beautiful brooches. The Cartier is said to have dominated the exposition with a display of more than 150 breath-taking items.

“The case of the brooch demonstrates the survival of 19th century historicism in the 1920s,” notes author Hans Nadelhoffer in the book, Cartier: Jewelers Extraordinary. “In addition to Persian, Chinese and Egyptian influences, the Cartier brooch during the Art Deco period in the form of fibula (dress clasp), was also to be enriched by 7th century Merovingian forms.”

Nadelhoffer pointed out that Cartier’s brooch designs were based in part on the study of designs in museums. Moreover as early as 1907 it was fashionable to secure a kimono or kaftan with a fibula brooch clasp. According to Nadelhoffer such an item had been featured as one of the wedding presents for the Queen of Spain.

The brooch in the Art Deco tradition sometimes included molded glass with gilt and silver overlay set in brass. Amber-colored glass was a popular setting along with the pale-Colored mineral cut of marcasite mounted on silver or white metal.

In France both Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels further developed in the Art Deco period of the 1920s and 1930s a double clip design which could be separated on either side of the neckline, or joined together as a single brooch.

Today both Art Nouveau and Art Deco designs in a striking brooch are very popular with collectors. Typically those brooches signed or identified by a leading maker are considerably more valuable than unmarked varieties.

Cutlines:

Gold and enamel brooch, rose-cut diamond pansy against blue background. (Skinner Inc.)

Art Deco platinum, sapphire, and diamond brooch. French-cut sapphires (Skinner Inc.)

Amethyst and diamond brooch, box marked Jays of London. (Skinner Inc.)

Etruscan Revival gold and intaglio brooch, Hallmark of Ernesto Pierret, Italy. (Skinner Inc)

Follow Us