By Robert Reed

By Robert Reed While the grand old pocket watch never got its start in the United States, it had certainly become a great American tradition by the end of the 19th century. It adorned the outfit of every stylish lady and sat in the pocket of every dapper gentleman.

There was a gleaming and engraved pocket watch for every taste, and both figuratively and literally there was one for every pocket book. The wealthy could plunk down more than $100 for a solid gold timepiece, or the thrifty could mail-order one for just one dollar.

The pocket watch, like the clock before it, got its commercial start in Europe. Initially such portable tellers of time were carried in egg-shaped and later round cases, both were highly decorative and often crusted with jewels. Delicate movements within the confines of the cases were crafted in Germany, France, and Switzerland and sold to the well-to-do during the middle of the 17th century.

As ‘time’ evolved the watch generally became flatter and less and less elaborate. Although Swiss mechanisms of refined automation were very much part of the market in the early 1800s, there was somewhat of a trend toward the less intricate. While the Swiss still offered finely enameled watches for export, other countries including England moved toward more standard models.

For those without the embellishment of enamel upon Swiss watches there was at first simply the opened faced watch. Such watches worked well but were subject to damage if the relatively thin glass face was broken. As an alternative makers developed a much more protective case involving a hinged metal covering which fit conveniently over the glass face of the watch. Its ruggedness was identified with the vigorous outdoor hunter and thus the name, hunting case. Given more limited production was the oddly called half-hunter case which involved a small glass opening in the metal lid for ’peeping’ at the watch face without actually opening the lid.

For those without the embellishment of enamel upon Swiss watches there was at first simply the opened faced watch. Such watches worked well but were subject to damage if the relatively thin glass face was broken. As an alternative makers developed a much more protective case involving a hinged metal covering which fit conveniently over the glass face of the watch. Its ruggedness was identified with the vigorous outdoor hunter and thus the name, hunting case. Given more limited production was the oddly called half-hunter case which involved a small glass opening in the metal lid for ’peeping’ at the watch face without actually opening the lid. Historically speaking, during the first half of the 19th century American-made watches made little impression on the rest of the world or even U.S. citizens for that matter. After many struggles and even an embargo on English made watches, American watch production at last began to be effective in the 1850s. An early leader was the Elgin National Watch Company in Elgin, Illinois. Out of more than 60 U.S. firms, the Elgin Company would ultimately become the largest manufacture of jeweled watches in America.

Time was finally on the side of American mass production. U.S. watches could not only be mass produced as the 19th century swept to a finish, the idea of interchangeable parts became industrial reality.

For all of their worldwide dominance, it is fair to say that the quality of American pocket watches varied greatly. The finest and most precise among them was the railroad watch which sought to achieve the then high standard of railroad timekeeping itself. Then and today they were considered about the best American watch ever made. However it took more than the image of a train engine to be an actual railroad watch.

“Many early watch manufacturers decorated their watch dials (and cases) with locomotives and other railroad scenes,” notes Dean Judy author of the book, 100 Years of Vintage Watches. “This, however, does not denote them to be true railroad grade or railroad-approved timepieces. Railroad standards that were implemented had nothing to do with the decoration on the case or the dial on the watch.”

At the other end of the pocket watch scale was the dollar watch. History was made in 1896 when Robert and Charles Ingersoll contracted with the Waterbury Watch Company. As a result the Ingersolls sold the watches via mail order for one dollar each. They followed their initial success with extensive marketing and advertising of the “reliable one dollar Ingersoll watch.”

There were other dollar watches available, of course, and their production became an industrial milestone.

One magazine advertisement in 1898 offered the dollar watch for the pocket or for something else. “Your choice of either pocket watch or the new bicycle watch and attachment,” said the notice. “The watch can be attached to (the) handle bar of any wheel at a moment’s notice.”

Writing decades later in 1969 author Louis Hertz observed that the American dollar watch “now has completely vanished from the marks of the trade.” However, Hertz concluded in the book Antique Collecting For Men that such watches as “examples of industrial progression deserve retention and commemoration.”

By the late 1890s major department stores and mail order catalogs offered a vast assortment of pocket watches for both men and women. Leading brands included El-gin, Hampden, and Waltham but standard generic workings were also available. The men’s watches came with very decorative cases. Embossed illustrations included horses, landscapes, water falls, deer, village scenes, buildings, birds, trains, sailboats, flowers and even horse and wagons.

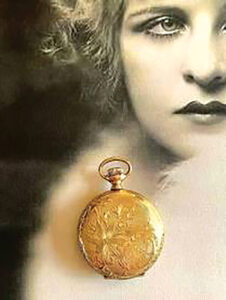

Women’s watches were brightly decorated with fine designs and sometimes flower arrangements. However often worn around the neck, they were much less likely to have the extensive illustrations of men’s pocket watches. A mail-order leader in the 1890s was the Lady Grange which came in a solid gold case and included a “Victoria” chain. It came with a silver trimmed oak case which could be locked with an accompanying key.

Such watches for women “changed with the styles” noted Anita Cole in the book Antiques. Some were attached “to a yard-long gold chain with a slide that allowed the watch to be tucked into the belt of the shirtwaist.” By the early 1900s other such watches “hung from its own pin on many a girlish blouse.”

In 1908 the Sears and Roebuck catalog was still pushing American-made pocket watches at American-made prices.

“Go into the very finest jewelry store in Chicago, New York, or any other large American city, and you will scarcely see an American made movement offered for sale. The movements they offer are all made in Geneva, Switzerland, but in such stores they get fancy prices.”

Nevertheless Sears still offered a full array of American pocket watches at the time including many “new model” solid silver examples.

Ironically some of the finest women’s watches, including dazzling Art Deco examples, were produced during the first quarter of the 20th century at a time when women were opting for another form of timepiece. Fashionable women had discovered the wrist watch prior to the 1920s although it was considered too feminine for men’s styles. After World War I servicemen found the wrist watch practical, it became popular enough to practically replace the pocket watch.

Just when the American pocket watch became fully collectible is difficult to say. However, in 1973 one national publication observed, “for many years collectors had not bothered much about American watches, but now they are considered important examples of pioneer methods of mass production.”

Follow Us