Weather Vanes have been around for over two thousand years and the earliest recorded weather vane was inspired by Triton, Greek God of the Sea. Cast in bronze, this life-size figure, with the head and body of a man and the tail of a fish, pointed his wand in the directions of the wind. He was placed above the Tower of the Winds, built by Andronikos in Athens during the first century BC

Archeologists have discovered bronze Viking weather vanes from the 9th century. They have an unusual quadrant shape, usually surmounted by an animal or creature from Norse fable. They were used as navigational aids, and were also popular on Scandinavian churches. These weather vanes can be seen even today in Sweden and Norway.

During the 9th century the weathercock was used on numerous buildings, and many believe that a papal decree demanded that every Christian church was to erect a weathercock, the emblem of Saint Peter and a reference to Christ’s statement to Peter on the eve of the Crucifixion “I tell you, Peter, the cock will not crow this day, until you three times deny that you know me” (Luke 22:34). Because of this story, “weathercocks” have topped church steeples for centuries, both in Europe and in America.

The 11th century Bayeux Tapestry depicts a scene of a craftsman attaching a rooster vane to the spire of the recently constructed Westminster Abbey and a medieval Roman hymn writer pointed out that the weathercock form typified watchfulness as well as religious office.

The 11th century Bayeux Tapestry depicts a scene of a craftsman attaching a rooster vane to the spire of the recently constructed Westminster Abbey and a medieval Roman hymn writer pointed out that the weathercock form typified watchfulness as well as religious office.

The word “vane” actually comes from the Anglo-Saxon word “fane,” meaning “flag.” which was used by kings, knights, or military commanders to indicate their rank. These banners which flew from the turrets of castles may have been the forerunners of to day’s weathervanes.

Eventually, metal banners were developed as they were more durable than the fabric flag and these were used by the early American colonists for their meeting halls and public buildings.

Because weathercocks were often three-dimensional they required more maintenance than the silhouette vane. The weathercock on Saint Paul’s Cathedral in London was restored and regilded from 1273 to 1461 before it blew down and was destroyed in the churchyard in 1505.

After the Great Fire of London in 1666, and the rebuilding of London, the weather vane was once again popular. The weathercock, heraldic-style banners, and arrows were used by the famous architect, Sir Christopher Wren, and his contemporaries.

The weather vane was extremely popular in America because weather forecasting was vitally important to the seafaring and agricultural lives led by the Colonists. Many residents erected a metal banner as a coat of arms over his home or farm.

America’s first documented weather vane maker, Deacon Shem Drowne, created the famous grasshopper vane which has perched on top of Boston’s Faneuil Hall since 1742 and the banner for Boston’s Old North Church (1740). In 1721 Shem Drowne created a golden cockerel from two kettles. It weighs approximately 172 pounds and is more than one foot thick. This piece is believed to be the oldest vane made in New England that is still in use (First Church in Cambridge, Congregational, United Church of Christ, Cambridge). Shem Drowne also built an Indian archer of hammered copper which was created for Boston’s Province House in 1716.

Thomas Jefferson attached the weathervane on Monticello to a pointer in the ceiling of the room directly below, so he could read the direction of the wind from inside his home, and George Washington commemorated the end of the Revolutionary War by commissioning a “Dove of Peace” weather vane from Joseph Rakestraw in 1787, for his estate at Mount Vernon.

Early wooden vanes were created by hand and the endless variety of forms affirms the artist’s individual sense of design. Full-bodied, three-dimensional examples were the most difficult to carve. Flat-bodied vanes were occasionally embellished with carved details.

Shortly after the Revolution, native tin and coppersmiths were devising weather vanes in shapes and patterns that surpassed their European counterparts. Unburdened by Continental tradition, these craftsmen could create for their customers vanes that exhibited wit, humor and delicate design.

By the end of the 18th century the weathercock had lost much of its religious significance. As a representation of the strutting barnyard tyrant, its broad tail could catch even the gentlest summer breeze and indicate the true direction of the wind for all to see.

Animals and fowl of every description appeared over farmhouses and barns throughout the young nation. Subjects were frequently related to the immediate locale. Buildings in coastal towns featured whales, codfish, swordfish, dolphins, mermaids, and square-rigged ships. Paul Revere placed a wooden codfish studded with copper nails for scales above his silversmith shop in Boston.

In the South, where English traditions were still observed, heraldic banners and standards were popular.

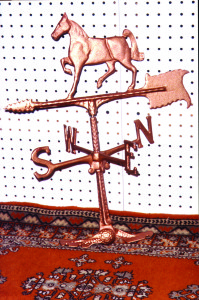

Farmers however, as they could not see the town’s vanes, erected their own. Being far from the local blacksmith, they invented their own designs. Breaking with tradition, the farmers created vanes in the shape of Indians, and wild and domesticated animals, especially horses.

In the early 1800s, Americans favored weather vanes in patriotic designs. The Eagle, Columbia, the Goddess of Liberty, George Washington on horseback, and finally the Statue of Liberty indicate the large variety of designs that adapted in the 18th and 19th centuries by commercial weather vane companies.

The weather vane became one of America’s first forms of sculpture. The vigor, boldness and ingenuity displayed by 18th century weather vane makers have come to be internationally recognized.

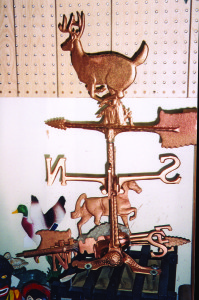

Beginning in 1875 vanes were mass-produced in metal, using wooden, hand-carved models. Manufacturers advertised hundreds of shapes in elaborate catalogs that reflected the growth of the United States; the railroad, fire-fighting equipment and farm specialization. However, many of the favorites continue to be tied to nature, in weather vanes of many different animals.

In the 19th century there were many weather vane manufacturers mass-producing vanes in dozens of designs. Some of the more famous makers were L. W. Cushing, J. W. Fiske, Harris & Co., A. L. Jewell & Co., and E. G. Washburne & Co.

The stationary metal vane or banner became popular as an architectural ornament during the second half of the 19th century. Victorians frequently used them on their Gothic Revival houses and buildings and the Victorian style copperwork is in great demand for the Victorian Revival homes of today.

Today, weather vanes are being rediscovered as an opportunity to express individuality, regardless of the “direction” in which it may lie.

Bird with fancy tail, wrought iron, paint traces, original V mount, bullet holes, may sell for $1000. Eagle, gilt copper, late 19th Century may sell for $4000. Indian, copper, molded Mashamoquet, full bodied figure, Indian chief, shaggy pony tail, short skirt, repousse detail, drawing bow and arrow, standing on arrow headed rod on abstract rockwork. c.1850 may sell for $7,975.

Further Reading: Myrna Kaye, Yankee Weather Vanes A. Needham, English Weather Vanes Museums: Heritage Plantation of Sandwich, Sandwich, MA

Follow Us