By Rosemary McKittrick

By Rosemary McKittrick And there’s many a story that could be told

Of the fine figureheads that were chiseled of old

On the dreary sands they crumble today

From Terra del Fuego to Baffins Bay.

–19th century naval officer

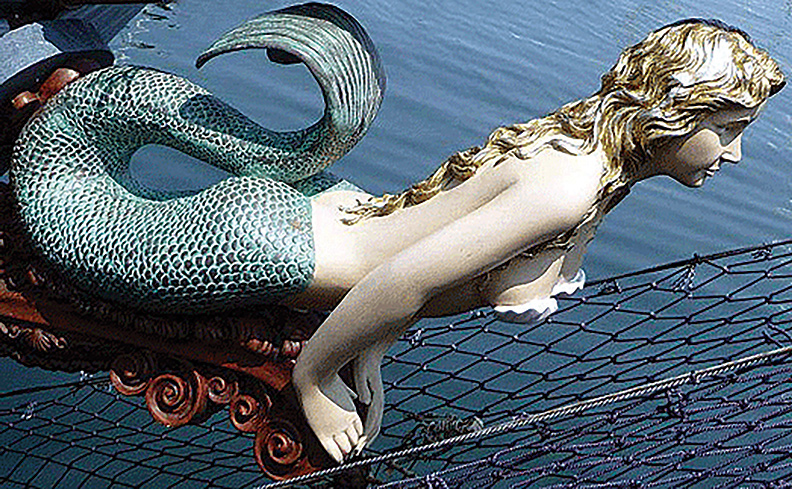

The golden-haired figurehead in her white and green gown seems confident and casual about her ability to calm Neptune. Battling the wind she embodies the spirit of the sailing ship as she looks down over the waves. Soothing the sea gods, she makes sure the voyage will be safe.

Fair-maiden figureheads, mermaids, mariners, and even twin sisters imbued the bows of early sailing ships with an almost human personality. The ship’s character and quirkiness were well known to the sailors who sailed them.

Often the maiden’s arm in these guardian spirits was extended to carry a wand or a weapon. The other arm might rest upon her bosom holding a rose or bunch of flowers. Some figurehead carvings were amazingly inventive. Others came from pattern books. Quality varied.

Eyes sometimes glared. Arms, necks and chins might be simplistic. Carving could be delicate, crude or conventional. Changes in the design of ships also affected the size, shape, and position of a figurehead.

Almost always, figureheads outlived the massive oaken ships whose bows they graced. The ships may be long forgotten but the figureheads themselves live on in museums, private collections and antique shops. In many ways it’s like trying to study the human body by only looking at the head. The biggest parts are missing.

The names of many of the self-trained, figurehead carvers are also long gone. Carvers saw themselves as artisans more than artists.

Used for thousands of years, bow ornaments have shown up on the earliest surviving Egyptian boats and rock drawings. Phoenician sailors also adorned the prows of their galleys with wooden likenesses.

Whether its ship’s figureheads, carousal animals or tiny toy creatures, whittling has always eased man’s anxiety and soothed his soul.

The golden period of sailing ships in the 19th century saw the height of bow decoration. Ships berthed at South Street, New York, in the 19th century picture giant hulls, rigging, and figurehead sculptures leaning over the wharf. Ships filled the harbor like cars filling a parking lot.

The design of a wooden ship’s bows determined whether the figurehead would be a full figure, half-length or only a bust. Sometimes only an ornament was used.

The figure might resemble the ship owner or his wife or children. Famous people like Davy Crockett and patriotic themes like the American eagle were also popular. Racial and gender stereotyping was plentiful.

Figureheads and other elaborate carvings adorned wooden sailing vessels until they disappeared with the slow but sure introduction of modern steam-powered steel ships.

The German Kaboutemannekes Sailors from Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Scandinavia believed that each ship had a resident sprite, fairy or brownie called a Kaboutemannekes. The spiritual creature lived in the ship’s figurehead and watched over the sailors on the boat. Among the tasks of the Kaboutemannekes was to guide the ship around rocks, keep it steady during storms, and protect the men from sickness. When ships sunk, it was believed, the Kaboutemannekes escorted the souls of the dead sailors to the underworld.

Follow Us