By Robert Reed

By Robert Reed One of the most enduring symbols in earlier America was the rooster. It was a dominate image for this country’s classic folk art including weathervanes, wood carvings, and windmill weights.

Later the traditional rooster would be crowing on an assortment of American-crafted things including hooked rugs, cookie jars and even salt pepper shakers.

Historians suggest that the rooster was one of the earliest choices for weathervanes designed in the United States and Canada. Prior to the 18th century it had been widely used in Europe on church steeples of the Christian faith. To Christians the rooster represented the New Testament’s account of Peter’s three-time denial of Christ when such an animal crowed twice.

The French referred to such a rooster image as a chantecler, other name variations included cockerall or often times in the case of a weathervane, the weathercock. By whatever name they were readily visible atop shrines, churches and barns throughout North America during the 1700s and 1800s.

Certainly one of the oldest rooster designs used in America was the copper cockerall which adorned the steeple of the Dutch Reform Church at Albany, New York. The symbol dated from the 1650s and made largely of copper. Another early rooster weathervane, crafted in 1715, stood atop the Rocky Hill Church, in Amesbury, Massachusetts. It too was riveted from sections of copper.

During the 1720s on of the most famous weathervane makers in New England, Shem Drowne, was fashioning rooster weathervanes in the rooster image. One of his best works was the giant Revenge Cockerel which stood atop the First Revenge Church of Christ. Said to be hammered from copper kettles, it weighed more than 170 pounds. History records it was blown down during a storm and crashed through the room of a nearby house landing in the kitchen.

At times the basic copper of rooster weathervanes was enhanced with sections of gold leaf and decorated further with yellow paint. By the 1790s such roosters were frequently painted and sometimes wood and metal were incorporated to form a complete united. On occasion rooster legs were make of wrought iron.

At times the basic copper of rooster weathervanes was enhanced with sections of gold leaf and decorated further with yellow paint. By the 1790s such roosters were frequently painted and sometimes wood and metal were incorporated to form a complete united. On occasion rooster legs were make of wrought iron. By the early 19th century the rooster weathervane remained popular and could be found made simply of wood or constructed of whatever metals were available. Typically the wooden roosters were finished with a paint coat of yellow or reddish brown. While the wooden versions could be repainted from time to time, often they eventually gave way to the ravages of weather. As a result it is difficult today to find prime examples of 19th century wooden rooster weathervanes.

Weathervane manufacturing had become a prosperous trade by 1850 and the strictly wooden rooster had been generally replaced with metal versions. In many ways the use of metal allowed for more creativity.

Typically such rooster weathervanes were the hand-made by a small group of craftsmen working together in the second half of the 19th century. “Usually only three of four craftsmen, often members of the same family, comprised a company,” according to Adele Earnest author of the book Folk Art in America.

“Usually a professional wood carver was hired to create the original wood model. The design might be adapted from a popular print. The piece molds were cast from the carving; dies into which two copper sheets could be hand-hammered and soldered together to create the three-dimensional (but hollow) weathervane.”

In some cases profiles were cut from hammered sheets and metal to form the rooster. The profiles were pierced so they would better withstand strong winds before being joined together. Some craftsmen used an original wooden form inside the sheets to provide a more substantial shape before joining the sheets.

Next came the painting which, like earlier practices, involved a base coat of yellow paint. However golden gilding was also added as a final touch to the metal, and it could be updated from time to time.

“The fact that copper was so easily hammered gave the artist a good chance to get texture into the features of the rooster,” noted Erwin Christen in The Index of American Design. “This was done more for the sake of variety than zoological accuracy.”

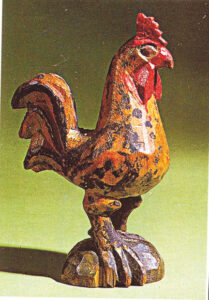

And while rooster weathervanes were popular in the latter part of the 19th century they were not the only form of the familiar barnyard animal. In Pennsylvania for example, carver Wilhelm Schimmel traveled the countryside during the 1870s fashioning roosters and other creatures from pine wood. Today prize examples of the painted works are found at the Henry Ford Museum and the Museum of American Folk Art.

Elsewhere there were roosters of chalk ware, and intricate roosters in whirligigs which often sat atop windmills in rural areas of the country. Additionally there were roosters used as targets in late 19th century shooting galleries, and even a brief attempt at carving roosters to go along with other animals for carrousel rides.

“It was hoped that novelty would attract trade,” explains Christensen. “However it was soon discovered the children invariably chose the horses and particularly the dappled kind. After that, the strange menageries, also including bears, reindeers, and giraffes, was abandoned.”

America in the 1890s witnessed a significant number of commercial companies in the business of manufacturing rooster-type weathervanes. Firms like J. W. Fiske, L. W. Cushing & Sons, E.G. Washburne Company and J. Howard and Company provided an endless variety of roosters. Some examples included hens, and some came with stylized pineapple finials which were said to denote hospitality.

Materials varied considerably shortly before the dawn of the 20th century. Wood was used on a very limited basis while the selection of metals everything from copper to zinc. There was also a trend toward use of cast iron at least for parts of the rooster weathervanes.

The 1890s also saw a rise in another form rooster, the mill weight. A major contributor was the Elgin Windmill Power Company of Elgin, Illinois. The firm used animal forms for many sizes of mill weights ranging from eight to 85 pounds. The cast iron images were typically from 15 to 18 inches tall. In practice they were individually attached to the windmill and used to pump water to other parts of the farm.

Elgin and others continued to make rooster-image mill weights into the 20th century, and while earlier examples were simply painted white later issues were sometimes given red and yellow detailing. Today such surviving figural mill weights, even those with slight surface imperfections, can be highly collectible.

As early as the 1930s the Pottery Guild of America had adopted the rooster’s wistful likeness for crafting cookie jars. In later years other cookie jar makers followed suit including Sierra Vista, American Bisque, Gilner, McCoy, and even California’s Twin Winton.

By the middle of the 20th century roosters of the past were being re-discovered as grand American folk art. Weathervanes and wood carvings were retrieved from playgrounds and attic trunks to be claimed as prized collectibles. Today such classic rooster images command major attention at leading shops and auction galleries.

Follow Us