By Robert Reed

By Robert Reed It might be difficult to determine the fairest armchair of all in historical America. There were many styles with many origins.

According to one expert writing many decades ago it could have been the Windsor armchair. Initially such chairs, with and without arms, were made in small villages in a certain region of England. However the American cousin of such chairs was, in the opinion of Harold Bond author of the distinguished Encyclopedia of Antiques, much more attractive.

In 1937, Bond maintained the American Windsor armchair crafted throughout the 18th century was “more graceful and more harmonious in proportion and design,” than the British version or practically any other kind.

Certainly America’s romance with the armchair developed long before that time.

There is evidence that some basic examples were in use in early colonial America. During the middle 1600s the few available armchairs were basically square with carved oak panel backs. Some armchair backs, toward the latter 1600s, were fairly elaborate with punched out stars or other symbols.

However, even by the dawn of the 18th century chairs in general and armchairs in particular were not all that plentiful among the majority of colonial families. A survey would likely have found them only in the more prosperous homes. When in use the large armchair “functioned as both a place to sit and as a symbol of patriarchal power…and would have been used by the head of the household,” notes author Charles Venable in the volume American Furniture in The Bybee Collection. “His wife may have had a lesser version of the same chair, while children probably sat on benches, stools, or even tree stumps.”

A majority of existing armchairs in America during this period were basical1y rather square with plain or carved oak backs. Certainly many in New England were characteristic of the so-called Wainscot chair with broad, solid back panels and a boxed bottom. In some cases the backs of such chairs were given elaborate gothic designs. Such chairs were to have been derived from ‘wain’ the German word for wagon and ‘schot’ or crossbow. Eventually the term applied to this European style chair that came to be crafted frequently in the colonies.

There was also the banister-back chair seen in the early 1700s with upright spindles. They appeared both with and without arms, and traditionally had four back spindles for support. Such spindles could be entirely flat or half round in appearance. Similarly there were basically slat-back chairs of that era, often made of ash or maple, which followed a very simple form.

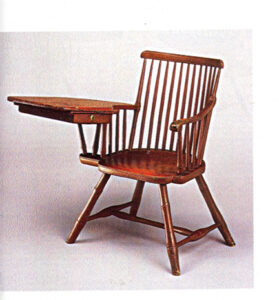

There was also the banister-back chair seen in the early 1700s with upright spindles. They appeared both with and without arms, and traditionally had four back spindles for support. Such spindles could be entirely flat or half round in appearance. Similarly there were basically slat-back chairs of that era, often made of ash or maple, which followed a very simple form. Additionally there was, as Bond had noted with favor, the American style Windsor chair that was a favorite in colonial homes from the early 18-century on for many decades. Distinctive and durable, most of the early American examples bore relatively thick turnings in their crafting. An adaptation of the Windsor armchair was the desk chair, which expanded to include a widened arm for writing, sometimes such chairs also had a drawer directly beneath the arm for books or writing materials. Others had a drawer instead at the bottom of the chair.

Toward the middle of the 18th century colonial America was enriched with beautifully crafted armchairs following highly admired Queen Anne and Chippendale styles. A prime example was Philadelphia cabinetmaker Solomon Fussell whose slat-back maple armchairs were the highest essence of Queen Anne design. Typically they employed six arched slats flanked by turned stiles joined to shape arms with scrolled terminals. Fussell’s finest works were created in 1740s. During that period William Savery apprenticed with Fussell and went on to make notable armchairs himself Savery’s armchairs with divided three lobe feet had exceptional merit and sold for significant sums at, ‘the Sign of the Chair, a little below the Market, in Second Street” in the city of Philadelphia.

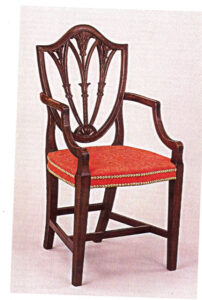

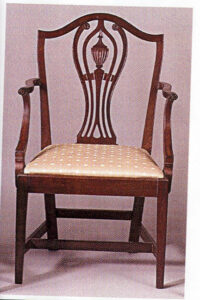

Talented craftsmen of Philadelphia tended to make a wide variety of chairs for a wide range of customers in the 1750s and beyond. Relatively inexpensive turned chairs were available for use in the lower and middleclass homes, as well as for service areas of the finer residences. The most costly and fashionable of all the Philadelphia chairs were the armchairs made of fine woods such as mahogany or walnut.

Some of the most striking of the Philadelphia chairs of the 1760s and 1770s offered wide balloon seats, richly carved shell motifs, and solid urn-shaped blacks. Among the elite were those with claw and ball feet, and stumped back legs.

Meanwhile in New York armchairs in the Chippendale tradition were in some favor with a tendency toward more solid splats in tapered backs. New York during that era was also witness to a number of Queen Anne style armchairs with vase-shaped splats, often a combination of walnut and walnut veneer over pine as well.

Historians note of a distinguished armchair made by Philadelphia chair maker Ephraim Haines early in the 19th century. Ephraim included the armchair with high rising French elbows in a set of black ebony furniture sold to financier Stephen Giard. For such work Haines charged the then staggering sum of$500, which was acceptable to Giard who was one of Philadelphia’s wealthiest citizens.

Back in New York City during the early 1800s arguably the nation’s most famous cabinetmaker, Duncan Phyfe, was busy making armchairs among other things.

Back in New York City during the early 1800s arguably the nation’s most famous cabinetmaker, Duncan Phyfe, was busy making armchairs among other things. In fact Phyfe and his shop of nearly 100 workers made a range of armchairs in the course of providing furnishings to the wealthy class of New York. However one of the most notable examples was fashioned after the ancient Greek klismos chair. This classic form reappeared in the Empire period at the start of the 19-century. In keeping with its popularity Phyfe’s workshop crafted a stylish scroll-back armchair in the enduring Greek tradition.

Still another armchair which attracted wide attention early in the 19th century was the type that would later been referred to as the Martha Washington chair. This upholstered armchair had a distinctive American appearance with tall back and slim tapered arms and legs. At the zenith of its popularity in New England, was sometimes known as a lolling chair meaning one for relaxing or reclining. While it was clearly a product of the Federal Period in America, the connection with the nation’s First Lady have never really been fully explained.

Whatever the reasons Americans maintained a sustained romance with beloved armchair, both foreign and domestic, for generation after generation.

Follow Us