By Robert Reed

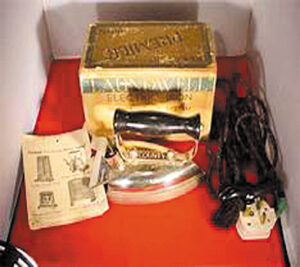

By Robert Reed Electrical kitchen appliances were mostly a 20th century deliverance for the homemaker. It was not that devices that not been invented. Henry Seely of New York City obtained a patent for an electric flat iron in 1882, and Dr. Schuyler wheeler developed an electric propeller fan that same year. But home electricity was not that plentiful.

As late as 1905, even those homes wired for electricity were largely limited to using it mainly for lighting. As noted by Charles Panati in Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things, at that time in history most power companies turned on their generators only at sunset, and they turned them off at daybreak. Thus the electric toaster, percolator, and iron had to function at night.

Electric toasters had appeared soon after the turn of the century, but as Panati points out they were “skeletal, naked-wire structures, without housing or shells. They lacked heat controls, so bread still had to be watched moment to moment.”

Landers, Fray and Clark had an electric coffee percolator on the market by 1908, Westinghouse had an electric frying pan in 1911, and Armstrong’s Standard Stamping Company offered a fancy electric broiler in 1916. Landers, Fray and Clark again lead the pace in 1918 with both an electric mixer and electric waffle iron. “Once electricity was available in a community, probably the biggest problem in selling electrical appliances in the early days was that there was virtually no-one to do repairs,” observes Linda Franklin, author of 300 Years of Kitchen Collectibles. “And undoubtedly many people were afraid of shocks and electrocution.”

During the 1920s most of these fears were overcome by the strong appeal of ‘modern living’ through printed advertisements. In 1925 an ad by the Edison Electric Appliance proclaimed that a Hotpoint Breakfast Set was a joy, “what could be more auspicious than an electric breakfast of waffles and coffee, prepared in a jiffy, at the table.”

When the Sesqui-Centennial International Exposition opened the following year it offered visitors that same shining image of modern living. At the Philadelphia site was an all electric house which included a vast array of electrical appliances including a toaster, waffle iron, mixer, iron, and even a burglar alarm. At almost the same time the first electric steam irons were being put on sale at leading New York City department stores. The price was a hefty $10 each, and they would not really catch-on with the public until the switch of clothing manufacturers to synthetic fabrics during World War II.

Meanwhile at other stores the electric pop-up toaster was being marketed by the McGraw Electric Company under the Toastmaster trademark. For $13.50 customers could own a device which used a lever to lower the bread into the toaster, one slice at a time.

During the 1930s the favored New Britain, Connecticut company of Landers, Fray and Clark became better known as Universal brand and delighted homemakers with chromium waffle makers, toasters, mixers, blenders, and irons.

“The minute I laid eyes on those good-looking Universal gifts, I knew what I wanted, ” beamed a smiling housewife in a colorful 1930s magazine ad. “They’ll help me so with entertaining and housekeeping…” Elsewhere in 1930s consumers could buy a two-slice Toastmaster toaster from McGraw Electric, a Waffle Master from Waters Genter Company, an oscillating fan with cast iron base from Diehl, and a Mixmaster with numerous attachments from Sunbeam Corporation.

Also during the 1930s the Waring Mixer Corporation offered a new blending device. Initially it was known as a vibrator and based on the invention of Stephen Poplawski of Racine, Wisconsin. At first it was mainly sold to bartenders for mixing drinks, but it would have a great future in the modern kitchen.

In 1937 the Sears catalog featured an entire range of Heatmaster electrical appliances including glass coffee maker waffle iron with chromium finish and Bakelite handles, and a sandwich toaster. Still other appliances were billed as, “modern, sparkling, beautiful, with graceful matched design, finished in gleaming chromium with natural walnut handles.”

Style was everything in the very early 1940s. Sunbeam, for example, offered a chrome toaster of “lovely oval design, the last word in modern styling by George Scharfenberg” in 1940.

Toasters, mixers and other electrical appliances were suddenly streamlined and sleek, mirroring the still popular Art Deco image. American Electrical Heater Company sold the stunning American Beauty iron beginning in 1940. It came with color Lucite, and black Bakelite handles.

By 1944 the world had all but ended a glorious new age of appliances. The Sears catalog proclaimed that year, “to send our fighters the arms and munitions they must have to fight our battles, we at home must do without many things we formerly enjoyed.” Following the statement was a long list which included most anything in the kitchen that was electric.

During the late 1940s and early 1950s there was a battle among manufacturers for consumers who were intrigued with even more advanced appliances. Sunbeam Mixmaster was finally able to produce a mixer with an amazing ten different speeds, and the Waring Company was about to introduce blenders for home use in designer-colors.

Typical modern kitchens of the 1950s and 1960s could boast all the basics plus four-slice toasters, stainless steel percolators, flip-flop oven broilers, and electric can openers.

Today “collecting early electric kitchen appliances can be a lot of fun,” according to Gary Miller and Scott Mitchell co-authors of the Price Guide to Collectible Kitchen Appliances. “They are both usable and attractive. Because they range from primitive to shiny, high-style Art Deco designs, they make wonderful focal points and conversation pieces.”

In recent years, Ellen Plante concluded in her book Kitchen Collectibles, that “prices are reasonable on electric appliances, for the time being, but expect prices to increase as collectors find merit in early examples. This especially will hold for those examples that achieved only limited success and, therefore, had small production numbers.”

Recommended reading: Price Guide to Collectible Kitchen Appliances by Gary and Scott Mitchell, Wallace-Homestead. Hazelcorn’s Price Guide to Old Electric Toasters by C. Fisher, H.J.H. Publications.

Follow Us