By Robert Reed

By Robert Reed While the experts all agree that the American bureau is a beautiful piece of furniture, they are not fully in accord about its origins.

The term itself was derived from the French word ‘burel’ which was used late in the 17th century to designate the woolen cloth used for covering the immediate surface of a crude form of writing desk.

Initially the bureau were little more than a table which supported a small chest. The chest could be moved backwards on the larger table base to allow a desk-like space for writing. By the early 18 century in England the bureau term became more or less accepted for a variety of writing furniture. Typically the piece incorporated a chest of two or more drawers.

In 1803, English furniture designer Thomas Sheraton noted in his Cabinet Dictionary that the term was “applied to common desks with drawers under them.” The Encyclopedia of Furniture by Joseph Aronson suggests that bureau was apparently the name given in England to the entire family of desk-and-drawer combinations. In American the same thing might be known simply as the secretary.

However, further adding to the confusion, decades before that in America the bureau term was generally accepted instead as a name for a four-drawer chest of drawers.

Consequently the word bureau meant different things to different groups. In this country generally it defined a sort of chest of drawers or more elaborate dressing table. Typical the American bureau had flaring French style feet with a scrolled skirt.

Consequently the word bureau meant different things to different groups. In this country generally it defined a sort of chest of drawers or more elaborate dressing table. Typical the American bureau had flaring French style feet with a scrolled skirt. As early as 1757 a probate of an estate in Virginia made reference to “2 Bureauo dress Tables,” while still another household inventory mentioned a single, “Buro Chamber Table.” Basically the bureau in America served as a storage unit of drawers with a table section for dressing, and perhaps smaller drawers above for accessories.

Not surprisingly the varied but attractive bureau most always found its way into the bedchambers of fashionable Colonial homes where it was used for dressing.

As the Federal period emerged in the early 1800s the bureau in America sometimes had a deep top drawer which could be used for storage of large items such as blankets or quilts. Besides the so-called tablet drawer, the piece may also have included smaller drawers.

Fancier bureaus made have had an elliptic sweep which meant rounded drawers sweeping backward in an oval pattern. Alterations to the standard design of the bureau, including changing the lines of the drawers, usually increased the price charged by the cabinetmaker considerably. The sweepingly rounded serpentine bureau, for instance, could raise the price by 50 to 100 percent more for the Colonial customer.

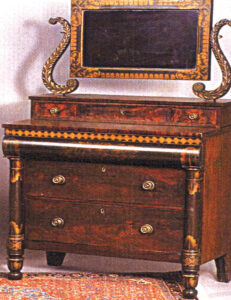

A Federal bureau from the early 19th century was often crafted from cherry or mahogany and may have included delicate bird’s eye maple inlay. Carving and stenciling were also sometimes added to enhance the appearance along with various veneer applications and brass fittings.

Still another variation of the standard bureau was the bureau table. Such an item was versatile enough for both storing and writing. The bureau table offered by classic English designer Thomas Chippendale often offered a case of blocked drawers along with a sliding tray drawer just above a kneehole space for the writer. Some Chippendale pieces provided a solid door which opened into a three-shelved interior. Meanwhile the bureau table offered by American cabinetmaker John Goodard, for example, allowed for both a kneehole desk space and an upper section bookcase.

Still another variation of the standard bureau was the bureau table. Such an item was versatile enough for both storing and writing. The bureau table offered by classic English designer Thomas Chippendale often offered a case of blocked drawers along with a sliding tray drawer just above a kneehole space for the writer. Some Chippendale pieces provided a solid door which opened into a three-shelved interior. Meanwhile the bureau table offered by American cabinetmaker John Goodard, for example, allowed for both a kneehole desk space and an upper section bookcase. Additionally the word bureau was also paired with an assortment of cabinets, flat top desks, and tallboy dressing furniture.

For the most part however the American bureau was mostly a distinguished and deeply appreciated assembly of drawers and compartments.

Antiques historian Sarah Lockwood later attributed four basic forms to the American bureau.

– A true front block bureau when the front boards were curved off into the center depression.

– A square front, when the drawer boards did not curve but were left square.

– A serpentine front when the blocks of the drawers gave way to a sweeping out-and-in curve. (Usually the most expensive of the cabinetmaker’s designs.)

– A swell or kettle front. When the curve swelled gently toward the center, it was a swell front. When the two lower drawers bulged out at the front and sides, it was a kettle front.

“All of these designs were made about the same time in America,” according to Lockwood.

Often the bureau stood beneath a handsome mirror, or in some cases a “dressing glass” sat directly on the bureau. The relatively delicate dressing glass was designed to swing in a frame. Later in the 1800s which was the onset of the Empire period the bureau fronts became heavier and straighter, likewise the dressing glass became larger and heavier.

Empire designs, ever larger and bolder, usually displaced the earlier slender brass handles, sometimes called willow brasses. Instead makers opted for glass or even wooden knobs on the drawers.

According to Lockwood the changing designs gradually called for larger and larger bureau drawers. Eventually the trend led to two tiers of drawers instead of a single tier. “And there you have the familiar bureau that has persisted ever since,” summed up Lockwood writing in 1926.

In recent years a major exhibition of American studio furniture was presented in the nation’s capitol of Washington, D.C. A major feature of the show was an eight-foot piece of furniture made of mahogany and other hardwoods. Identified as a cross between a desk and a chest of drawers complete with secret compartments, it was titled the Bureau of Bureaucracy.

Follow Us