By Maureen Timm

By Maureen Timm One of the really neat things about music, and there are many, is that it reflects the times. Lyrics tell how people feel and about the events of the period. In many ways music gives us a more accurate picture of people and events of the period than any other method available.

The Catholic Church was the nurturing place for the greatest early contributors to Western music. The earliest music scores were written by hand, some as carefully wrought as the illuminated literary manuscripts produced by monasteries in the Middle Ages. Musically, they offered minimal information, giving note-pitches and word syllables under the relevant note. There was no indication of expression, softness or loudness, and no bar lines to indicate rhythm. It required scholarship to write such manuscripts, so they tended to be collected at wealthy and important musical and religious centers like Notre Dame or Venice; most European courts had their own collections, too.

Music printing was invented in 1501 by Ottaviano Petrucci. His system was not much less laborious than the old manuscripts and it was around 1528 that the Parisian Pierre Attaigant developed a system more suited to mass production, which caught on in Italy ten years later. These early printed manuscripts still lack expression marks, dynamic instructions and bar lines. Even with the new technology it was still cost-effective only to produce collections of Mass settings, motets and so on, sometimes by a single composer, sometimes by several; and the technology was more readily available in continental centers like Venice, Rome and Paris than in England, where manuscripts continued to be the main currency of written music well into the 16th century. By the 18th century printing was commonplace, yet some musicians still preferred working with manuscripts; typed music was sometimes hard to read, especially the values of the shorter notes, and opera houses preferred manuscripts because they were easier to amend. Some composers also believed that it was easier to avoid piracy if their music remained in manuscript. So Italian composers usually had their music printed outside the Italian states, if they had it printed at all.

Sheet music publishing was well established in the US by the early 19th century. Most of the music was printed with engraved plates, although in the 1820s some music was published using the lithographic process. Lithography was not very common until the 1840s, when the development of chromolithography made illustrated title pages economically feasible.

Sheet music publishing was well established in the US by the early 19th century. Most of the music was printed with engraved plates, although in the 1820s some music was published using the lithographic process. Lithography was not very common until the 1840s, when the development of chromolithography made illustrated title pages economically feasible. It is interesting to note that many of the Confederate imprints were lithographed – a process that requires less equipment and materials. Metal was, of course, a commodity required for the war and would have been very scarce at that time.

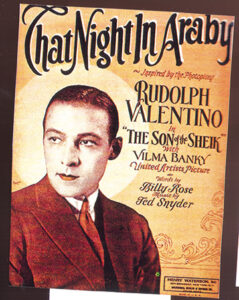

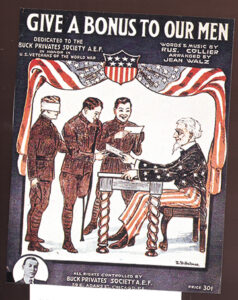

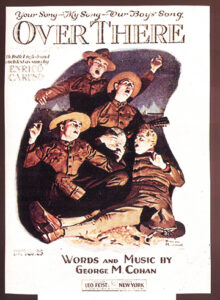

The period after the Civil War saw a great increase in music publishing activity. The stereotype process allowed publishers to issue huge numbers of music for mass consumption. Significant numbers of sheet music continued to be issued in the 20th century, centering around the area of Manhattan known as “Tin Pan Alley.” Many “hits” emanated from publishers such as Leo Feist, T.B. Harms, Irving Berlin, Shapiro & Bernstein, Von Tilzer and M. Witmark. Sheet music became so popular that it was even issued as supplements to newspapers.

With the rise of parlor music in the 1860s came a realization on the part of music publishers of the commercial value of printing advertising on pages of music. Companies even issued series of sheet music to help advertise their products, notably the Emerson Drug Company’s promotion of Bromo-Seltzer. During World War I publishers even promoted the war effort by using the margins of the music for such slogans as “Food will win the war, don’t waste it.”

Identifying the date of publication for music from this period is sometimes difficult. There has been considerable bibliographic interest in the printing and publishing of music in the 18th and early 19th centuries, but little bibliographic data is available about the publications from 1825 to the Civil War. Most of the publications bear some kind of copyright statement, but these statements are not universal in the publications of the period before the enactment of the first US copyright law in 1871. Also, because the music was engraved on plates, the publishers kept the plates in storage for long periods of time and printed new copies as they ran out of stock.

1601-1776 – The Colonial Era

1601-1776 – The Colonial Era Religious music was the first music of early colonists. Traditional English hymns were brought to America. Pilgrims from Southhampton and Plymouth brought with them the “Ainsworth Psalter” imprinted in 1612 in Amsterdam. It was used until 1667 when “The Bay Psalter” was adopted. Benjamin Franklin wrote and published a book of Ballads. Operas appeared. “A Mighty Fortress is our God,” and “Yankee Doodle” are good examples of this period.

1776-1860 – Revolutionary War/Post Colonial Era

The printing of individual items of music began in North America only after the Revolution. Music still closely linked to England. “The Stars Spangled Banner” was written in 1814. Other sons of this period include “Rock of Ages,” “America,” “Oh Shennandoah,” “Drink To Me Only With Thine Eyes,” and “Johnny’s Gone For a Soldier.” Folk music and ballads were the rage. Negro spirituals and slave music came from the African slaves.

1860-1900 – Civil War/Reconstruction Eras

Popular music just before and during the Civil War concerned itself with political and military events. Some of these songs included “Amazing Grace,” “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “Dixie,” “When Johnny Comes Marching Home Again,” “Old Black Joe,” “Carry me Back to Old Virginny,” and “Marching Through Georgia.” Religious songs were popular including “He Leadeth Me,” “Gimme that Old Time Religion,” “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen,” “Go Tell it on the Mountain,” and “My Faith Looks Up to Thee.” Folklore music started during this period and included the music of the American Indians, Black Americans, mountaineers, cowboys, lumberjacks, sailors and others.

One of the difficulties of caring for sheet music collections is that they tend to be treated as printed ephemera. Music was intended to be used, and people did exactly that. It may have rested on the music rack or in the piano bench, but most people played or sang the music. Anything that is used constantly will show signs of wear. Some items survived better than others. Much of the music printed from engraved plates in the 19th century is in fairly good condition because the paper was usually made of rags rather than wood pulp. Paper that was used for printing from engraved plates tended be a little thicker than paper used for ordinary purposes. Music printed on the cheap paper made of wood pulp tends to become very brittle, even in a short period of time.

One of the difficulties of caring for sheet music collections is that they tend to be treated as printed ephemera. Music was intended to be used, and people did exactly that. It may have rested on the music rack or in the piano bench, but most people played or sang the music. Anything that is used constantly will show signs of wear. Some items survived better than others. Much of the music printed from engraved plates in the 19th century is in fairly good condition because the paper was usually made of rags rather than wood pulp. Paper that was used for printing from engraved plates tended be a little thicker than paper used for ordinary purposes. Music printed on the cheap paper made of wood pulp tends to become very brittle, even in a short period of time. Many collectors are not as interested in the music as they are in the artwork on the covers. These are most impressive. Some noted artists such as Pfeiffer, Barbelle, Starmer, F. Earl Christy, Rockwell and many others must have made difference in the sale of sheet music. These artists have long been overlooked for their beautiful and sometimes amusing artistry. Some collectors like to frame sheet music which has a particularly attractive cover. Some prefer to collect those which have photos of stars, musicals, movies or entertainers such as Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor. Others prefer W.W.1, W.W.II, pre 1900 or any other categories which might be of particular interest to them.

Good care of sheet music is a must. It should be stored in an unsealed plastic bag so it can breathe. The pre 1900 sheets and Sunday supplements should be given extra care, as the paper used at that time was brittle and perishable.

Collectors’ Prices may vary in different parts of the U.S. “Over The Rainbow,” whole cast pictured on cover, may sell for $30. “So Long Mother,” Al Jolson, World War I soldier, Jerome Remick, may sell for $22. “Born to Lose,” Eddy Arnold, 1943, may sell for $9.00.

Follow Us