By Barry Krause

By Barry Krause Antiques have been repaired since they were first made, first by their makers themselves when customers brought damaged examples back to their original creators for expert repair.

Later, antiques were repaired by anyone, qualified or not, as wear and age harmed them over the years. So, when we are offered an old object as “repaired,” it doesn’t necessarily mean that it has no value today, only that we must determine if the repair “makes sense,” and learn when the repair was done and, ideally, for what purpose (to fix broken parts, to deceive collectors, etc.).

It isn’t always true that “an old repair is a good repair.” Sometimes it is, other times it isn’t. An old repair job may be shabby and hurt the value of an object. A modern repair can be superbly done and enhance the value.

Sixty some years ago, repairing antiques was big business. Here are a couple of ads that appeared in antique collector magazines of that time, offering repair chemicals for sale at prices that any collector could afford.

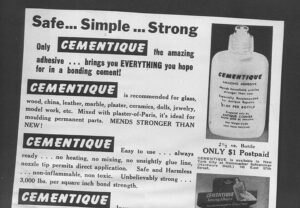

“Cementique” was “recommended for glass, wood, china, leather, marble, plaster, ceramics, dolls, jewelry, model work, etc. Mixed with plaster-of-Paris, it’s ideal for molding permanent parts,” says the ad by Antique Corner of South Bend, Indiana.

“Safe and Harmless … Unbelievably strong … 3,000 lbs. per square inch bond strength … Comes packaged in a squeeze-type plastic bottle, usable to the last drop.”

Cementique was guaranteed and “sold by leading dealers everywhere,” but, if you couldn’t find it for sale locally, you could order it from Antique Corner by mail for $1, postpaid, in a 2 ounce bottle, shipped directly to your home.

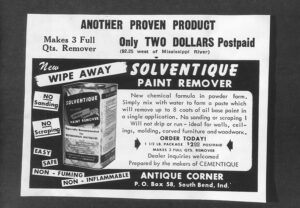

Cementique was guaranteed and “sold by leading dealers everywhere,” but, if you couldn’t find it for sale locally, you could order it from Antique Corner by mail for $1, postpaid, in a 2 ounce bottle, shipped directly to your home. The same firm sold “Solventique,” a paint-removing chemical in powder form which, when mixed with water, formed a paste that “will remove up to 8 coats of oil base paint in a single application,” and “ideal for … carved furniture and woodwork,” which makes us cringe to think about the many pieces of painted old furniture that have been ruined by stripping off their original paint by later generations of owners with the hope of making them “look better.”

Soventique was sold to the public in packages of either 1 1/2 pounds or 1/2 pound weight, it’s a little unclear from their ad copy, at $2 postpaid, or $2.25 if delivered west of the Mississippi River, in 1956.

Supposedly one such box of Soventique made three quarts of paint remover, enough to strip a fortune in antique painted furniture if you chose to do so. Arts-and-Crafts furniture of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was only a half century old in the 1950s, not considered true antiques by many dealers and collectors then, so we might expect them to “improve” the appearance of such otherwise “junk” old furniture by taking off its chipped paint and refinishing it with a nice, new coat of varnish or wood stain.

That’s why authentic, unrestored old painted furniture is in high demand today, with prices that would amaze people of just fifty years ago. It’s also why it gets a little harder to detect repainted repairs, if such work was done so long ago that it has begun to age itself, not usually enough to fool the experienced collector, but maybe with some acquired patina after repairs to trick a novice into believing that it really is the paint put on when the object was first made.

Some great guide books on repairing antique furniture and other old collectibles were written in the 1950s by experts in their fields. Many of those books are worth reading today for helpful tips on what to look for in suspected repairs, circa 1950s, that are sure to show up sooner or later when we go shopping for antiques with or without alleged repairs.

Follow Us