By Maureen Timm

By Maureen Timm Nothing can match the fantasy of a Christmas tree glowing with old glass globes and whimsical glass figures, reflecting the brilliance of the Christmas tree lights.

The first recorded account of a decorated Christmas tree is found in a Strasburg, Germany manuscript dated 1605 which reads: “They set up fir trees in the parlors…and hung upon them roses cut from many colored paper, apples, wafers, gilt-sugar, sweets…”

Tin ornaments were, along with blown wax ornaments, among the earliest manufactured Christmas tree decorations. The earliest tin ornaments date from the latter part of the 18th century. These were cast from a very soft tin and lead alloy by German Tin-smiths. Usually made in geometric shapes, each one was multifaceted to catch and reflect the dancing light of nearby candles.

As early as 1800, wax figures began to arrive in America. These were cast in molds by German toy makers. Wax representations were made of the baby Jesus and four-inch Angels floated in the air with the help of invisible thread and cardboard or spun glass wings.

Some of the most fascinating ornaments manufactured for the Christmas tree were the little silver and gold embossed cardboard ornaments. Called by their city of origin, they were manufactured in a variety of shapes. Animals, for example, included all sizes of fish, bugs, birds, camels and elephants. Dresden reindeer drew a sleigh candy box and Dresden animal heads often were made with attached bags for candy. There were also cats, moose and horses.

Another popular Dresden category was transportation. Dresden ships ranged from sailboats to paddleboats and ocean liners. Sleighs were elaborate and carriages were luxurious enough for royalty. Dresden zeppelins were prevalent even before World War I and were marked “Germany.”

Another popular Dresden category was transportation. Dresden ships ranged from sailboats to paddleboats and ocean liners. Sleighs were elaborate and carriages were luxurious enough for royalty. Dresden zeppelins were prevalent even before World War I and were marked “Germany.” An amazing amount of detail was pressed into these tiny ornaments which ranged from two to six inches high. They were made in several pieces. The animals, for instance, were actually two matching halves, embossed and cut out in the same stamping operation.

When they were dry, the separate halves were given to the cottage workers for finishing. The two halves of a horse’s head, for example, would be glued together and ears were then glued into pre-cut slots, and a bridle made of pressed paper was set in place. Little sleighs or carriages would be upholstered and silk threads added for the coachman’s reins. Cotton batting smoke was added to ship’s smokestacks, and a rudder and paddle wheel had to be pinned on and three dimensional cabins glued to the deck.

Most of these embossed cardboard ornaments were made between 1880 and 1910 and very few examples remain, although thousands were produced.

The little village of Lauscha in Germany was the center for glass ornament Making. Only 60 miles from Nuremberg, it became the glass making center in 1597. Protestant glass makers, fleeing religious persecution in the German province of Swabia, established themselves in Lauscha where they could utilize the natural resources of wood, limestone and sand to produce household glassware. Under a grant from the Duke of Coburg, they built the first “Glass House” and as the trade progressed they began to produce glass toys, pharmaceutical items, bulls eye glass for windows, as well as the usual utilitarian glassware.

The Lauschans began making thick-walled balls called “kugels” which they finished inside either with lead or zinc to achieve a shimmery effect. They soon discovered they could produce a striated effect by swirling the lead solution inside the kugel and finish it by adding colored wax to enhance the luster of the ball. The kugels were corked and a loop fitted through the cork for hanging. The finish on the kugels was mirror-like, but they were so heavy they had to be suspended from the ceiling.

The Lauschans began making thick-walled balls called “kugels” which they finished inside either with lead or zinc to achieve a shimmery effect. They soon discovered they could produce a striated effect by swirling the lead solution inside the kugel and finish it by adding colored wax to enhance the luster of the ball. The kugels were corked and a loop fitted through the cork for hanging. The finish on the kugels was mirror-like, but they were so heavy they had to be suspended from the ceiling. In 1867 a gas works was built in Lauscha. This new facility provided a regulated flame that enabled them to produce thin-walled glass products and they soon began creating many shapes, relying increasingly on the skill and artistry of the mold-makers. It is estimated that over 5000 different molds were made between the 1870s and 1940.

All family members shared in the final painting and decorating of the ornaments. By the 1920s German ornaments were painted by mouth-operated air brushes. On some ornaments Latin adhesive was applied and then sprinkled with gold, silver, or glass dust, or tiny beads called “Venetian Dew.” To achieve a shimmering effect of snow, the ornament was dunked into a solution of gelatin and starch.

Market day was Saturday and traditionally the women brought ornament boxes and sacks in baskets by train to Sonneberg which was the central depot for both ornaments and toys.

Ornaments became more elaborate as time passed, both in design and trim. Embellishments included the use of silk thread, chenille, tinsel, wool-thread, swags, tassels and crinkly wire.

Chromolithography, invented in England and adopted by German printers, provided inexpensive color pictures for the public. Suddenly, the public were collecting them in scrapbooks and they became known as “scraps,” and Christmas scraps were hung on many trees in those days.

Tissue paper honeycombs were made around 1900. Balls were followed by bells, and later, wreaths and baskets were introduced.

Christmas Crackers are an important Christmas tradition in England where they were originally made. Although they made the first and longest crackers, the Germans and French made the most elaborate. An 1890 American catalog shows crackers decorated with dressed paper dolls, full sized scrap angels, busts of the current Kaiser, and one cracker disguised as a sausage.

In America, crackers were used as tree ornaments, but eventually they were used at both Christmas and Birthday parties.

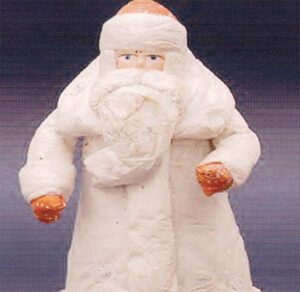

Many early trees were decorated with ornaments made of cotton wool. Numerous cotton batting ornaments were made in Lauscha and Dresden, where glass and paper ornaments were made, and some were assembled in America.

Families of home workers cut Santa Claus figures, angels and snow fairies from thin layers of cotton batting and folded and glued them over a wire or cardboard frame. They glued shiny printed faces of Santa or Angels, or little girls with curly hair to the cotton and buttons, or embossed gold paper wings for the angels. When the little figures were completed, glue was spread on the surface and sprinkled with sparkling glass particles to give a snow-covered effect.

Tinsel, invented by the French and originally called lame’ was used to decorate military uniforms. Lame’ was made by pulling silver-plated copper through diamond dies and fashioned by the Germans for tree ornaments. Some of the largest and most unusual decorations that hung on New England trees around the turn-of-the century were large, realistically painted papier-mâché fish. Each fish, which could be six to fifteen inches in length, had a large round trap door on one side which could be opened to reveal novelties and candy. These were made in the late 1800s by German manufacturers, who had perfected the technique of covering molded papier-mâché forms with a thin, smooth, lightweight plaster like surface that was particularly receptive to finely detailed painting.

The ornament for the top of the tree was always important. Five inch tin stars and Angels with wax heads and long pleated metallic foil skirts were made in Nuremberg at the end of the 19th century. At the same time, blown-glass Christmas “treetops” became available. Made by the German glassblower’s, they were the crowning point for the tree. A graduated series of balls, one above another, with a spike on top and varied reflector surfaces were pressed into each ball, and the whole ornament was free-blown from a single piece of glass tubing.

The most popular ornament for the old fashioned candlelit tree was the big wax Angel, often suspended by a fine wire just above the tree. These angels were wax covered papier-mâché figures made in Nuremberg in sizes ranging from four to eleven inches high.

In 1908 honeycombed paper bells began to appear on American trees along with red and green crushed crepe paper garlands that have been used to decorate Christmas trees, store windows and homes for many years.

After World War II German production ceased entirely and ornaments were produced locally. In the U.S. materials for making decorations were no longer available, but clear glass ornaments with a few bands of colored paint were manufactured.

After the war, consumer demand increased, and Germany again produced glass Christmas ornaments. These products can be found marked U.S. Zone Germany, USSR, and West Germany.

Christmas ornaments seem to satisfy a longing for the old sense of magic and excitement one felt as a child. Certainly, their delicate beauty and intrinsic charm will continue to delight generations to come.

Follow Us