From our earliest history, weaving and quilting bedcovers has been a medium for creative artistry. Since quilting became elevated from a home craft to a respected creative art, it also has become appreciated as a textile antique for its symbolism.

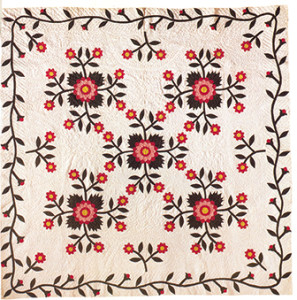

European immigrants brought not only quilts to the colonies, but also quiltmaking skills that developed and flourished. Eventually, the quilt made for winter warmth evolved into a collectable. Some, like an Eagle quilt together with a symbolic dove and intricate squares of flowers and vegetables and American flag, symbolize hope for peace during a time of unease then and now. This Baltimore Quilt, (c. 1840s) is made entirely of cotton, and incorporates unusually fine aesthetic elements of design and color.

The Stars and Stripes and the American eagle appear in countless 19th century quilts. A popular song of the century, “I was seeing Nellie home; It was from Aunt Dina’s Quilting Party, I was seeing Nellie home,” expressed a convention of women working in sewing circles for religious or charitable causes. The friendship quilt, created usually by neighbors or members of a group, church or family became a tangible example of how the women bonded to each other. Objects of both utility and beauty, quilts became documents revealing the values of the needlework of these friends.

As early as the War of 1812, the patriotic quilt became beloved and cherished. During the War of Mexican Independence (1846-48) and especially in the Centennial celebration in 1876 such quilts were publicly displayed with pride.

Many women who had been making tiny stitches by hand turned to the sewing machine when it became available just about the time commercial quilt patterns became available. In this exhibit, we see how the album quilt became popular between 1845 and 1855 in Baltimore, Md. While these patterns limited the ingenuity of theme and composition, women could still sign the quilt and add a touch of originality. In this exhibit, Texas women added a reference to their state by incorporating a red “lone star” into their designs.

Many women who had been making tiny stitches by hand turned to the sewing machine when it became available just about the time commercial quilt patterns became available. In this exhibit, we see how the album quilt became popular between 1845 and 1855 in Baltimore, Md. While these patterns limited the ingenuity of theme and composition, women could still sign the quilt and add a touch of originality. In this exhibit, Texas women added a reference to their state by incorporating a red “lone star” into their designs.

Quilters work with three layers of material, a center batting, and a backing sewn together. Among quilting styles developed between 1750 and 1825, wholecloth or calimanco quilts were made from lengths of fabric that had not been pieced into a design. Instead, the lengths were woven on narrow looms and then stitched together. The fabric was given a glossy sheen by being run through a roller. Stitching through all the layers of cloth created the decorative pattern.

During the Industrial Revolution, men became professional weavers in shops that specialized in coverlets. By the 1820s, a Frenchman named Jean Marie Jacquand patented a loom attachment that used punch cards to control yarns. This made it possible for professional weavers to control the yarns. Certain detailed patterns could be mass-produced. These usually had patriotic symbols, architecture, flora and fauna, and even portraits of patriots.

By mid-19th century, machine powered looms turned yarn into fabric. Roller printing was developed in 1815, and it was not long afterwards that the patterns on American quilts were roller printed. An English chemist, William Henry Pekin, experimenting with synthetic dyes created reds, purples, greens and oranges. Before long, American quilters were using vibrant colors and intricate patterns. By 1880, Philip Schum, a German immigrant, had a weaving business in Lancaster, Penn.

Among the favorite quilts is one by Linda O. Lyssett. She longed to leave her mark on history, and in one simple unpretentious quilt she created a medium that would outlive even many of her husband’s houses, barns and fences. She signed her name in friendship onto cloth and in her own way wrote: “Remember Me.”

Follow Us