By Robert Reed

By Robert Reed You certainly didn’t have to be Irish to send a postcard of St. Patrick’s Day greetings in early 20th-century America, and you didn’t have to be Irish to enjoy them.

Usually there was a good bit of blarney in the colorful cards that served to salute Ireland’s patron saint on March 17. One card in this collection is “From a certain girl, to a certain boy, Wishing him St. Patrick’s Joy!” On the reverse it is inscribed with an Irish greeting from an American girl, “call me sometime.” It is dated 1914.

St. Patrick’s Day is a church holiday in Ireland, and it honors the man credited with bringing Christianity into the Emerald Isle, and driving the snakes out.

Historic records show St. Patrick was not born in Ireland, but was captured by pirates and sold in Irish slavery sometime prior to 400 A.D. Later as a missionary in Ireland, St. Patrick is said to have used the shamrock, with its three separate leaves, to explain the Holy Trinity. Consequently the shamrock, a dwarf form of white clover that is native to that country, has always been one of the symbols of the annual celebration.

And the celebration of the Irish holiday has been “Americanized” for more than two centuries. According to the standard reference, The American Book of Days, this country’s first St. Patrick’s Day parade was held in Boston on March 17, 1737. When the British evacuated that city in 1776, George Washington reportedly selected “Boston” as the password for the day, and “St. Patrick” as the proper response.

New York City began hosting mammoth St. Patrick’s Day parades in the 1770s, and they have continued to draw crowds of well-wisheers ever since.

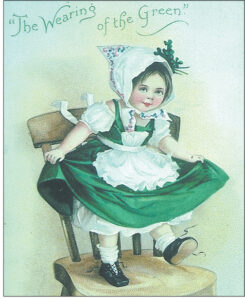

By the late 19th century, the celebration of the Irish-born event was widespread in the United States, and the “wearin’ of the green” became popular on that special day, as did extending greetings to others.

Private printers and publishers in the United States were granted permission to produce their own postcards by 1898, and after the turn of the century they became a means of mass communication for greetings.

The zenith of postcards in general, and St. Patrick’s Day cards in particular, came generally between 1907 and 1914, following the government’s decision to permit handwritten messages on the address side of a penny card, and before the mass-marketing of folded greeting cards complete with envelope.

The zenith of postcards in general, and St. Patrick’s Day cards in particular, came generally between 1907 and 1914, following the government’s decision to permit handwritten messages on the address side of a penny card, and before the mass-marketing of folded greeting cards complete with envelope. During that era, leading postcard artists such as H.B. Griggs, Mary Evans Price, Samuel L. Smucker and Frances Brundage teamed up with leading publishers for some stunning St. Patrick’s Day results.

The cards drawn by Ellen Clapsaddle, with her appealing Irish children, charming young women in bonnets, and even Baby Irish, were classic.

Among publishers, some of the best Irish holiday cards came from the Winsch Publishing Company in the U.S., and Raphael Tuck Publishing, which had offices in London, Berlin and New York.

Besides the traditional shamrock and children, St. Patrick’s Day cards also often featured the leprechaun, or at least his fabled top hat. Irish legend said this fairy in green could reveal the location of a pot of gold if he could be caught by some lucky person.

Other significant symbols used by artists included versions of the harp—a white one appears on the national flag of Ireland—clay pipes and outdoor scenery.

Frequently the cards carried non-English but ageless slogans such as Beannact Dia leat (God bless you), and the famed Erin go braugh (Ireland Forever).

Ironically, some of the best St. Patrick’s Day cards were printed in Germany, Italy and England—not Ireland. And they were marketed, not in the country of the legend, but in America.

Follow Us