by Roy Nuhn

by Roy Nuhn

“Chim-chim-ney, chim-chim-ney, chim-chim charee, a sweep is as lucky as lucky can be. Chim-chim-ney, chim-chim-ney, chim-chim-charoo, good luck will rub off when I shake hands with you.”

Remember that song from Disney’s 1964 movie hit, “Mary Poppins”? The film and the tune romanticized the chimney sweep of old. Actually it was a very dangerous and dirty job. There was nothing romantic about it in the real world.

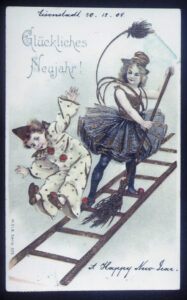

Artists illustrating New Year’s Day postcards during the earliest decades of the 20th century were very fond of creating allegorical scenes portraying the passing of the old year and the arrival of the new. Transitions from the worn-out old to the spanking new were symbolized by such pictorials as a “1906” trail passing by a stranded “1905” train and a “1908” balloon rising while “1907’s” slowly sinks to the ground.

Another image of this idea was chimney sweeps, a theme found on New Year’s Day postcards for about 20 years. Sweeps were especially symbolic of the notion of sweeping away the dust and dirt of the old year so that the new year could arrive shiny bright and minty.

Another image of this idea was chimney sweeps, a theme found on New Year’s Day postcards for about 20 years. Sweeps were especially symbolic of the notion of sweeping away the dust and dirt of the old year so that the new year could arrive shiny bright and minty.

Actually, English and American custom during the 19th century and a short ways into the next held that nothing was to be removed from the house on New Year’s Day. The chimney then had to be swept clean because it was through the flu that good luck for the new year arrived! The chimney sweeps who performed this yearly ritual were long an important part of New Year’s holiday tradition and lore.

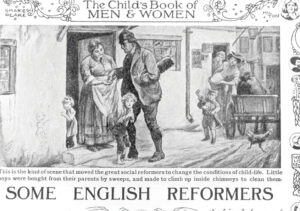

Though popular literature and music always portrays them as happy, go-lucky sort of fellows, in reality chimney sweeps were sickly, impoverished lads, usually younger than 13 years of age. They were short, slightly built children who rarely lived long enough to become teenagers, never mind young men.

Though popular literature and music always portrays them as happy, go-lucky sort of fellows, in reality chimney sweeps were sickly, impoverished lads, usually younger than 13 years of age. They were short, slightly built children who rarely lived long enough to become teenagers, never mind young men.

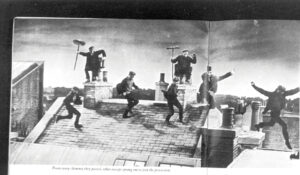

During the 19th century and a little bit into the 20th, chimney sweeps played an important role in England and on the continent. Fireplaces in the congested cities and crowded villages of the Old World were the only source of heat and the only way to cook.

The homes of the poor had one; the well-to-do, middle and upper classes boasted of several – often one to a room. Soot built up quickly with such heave usage, and chimneys had to be rregularly cleaned. If they weren’t, then eventually a fire broke out and, in those days before modern fire fighting equipment and technology, this meant a strong possibility of an entire block of homes or a neighborhood being burned to the ground.

The unpleasant and potentially fatal job of sweeping these chimneys was performed in merry olde England by members of the lower class. Sweeps were paid so poorly and labored under such horrible working conditions that it usually came down to the question of whether starvation, disease or injury would do the poor boys in first!

The young boys who worked as chimney sweeps were usually foundlings or discards from families who couldn’t afford to them. They lived short lives and worked from sunrise to sunset, | seven days a week. Tuberculosis, blindness, as well as malnutrition, were their common inheritance.

The young boys who worked as chimney sweeps were usually foundlings or discards from families who couldn’t afford to them. They lived short lives and worked from sunrise to sunset, | seven days a week. Tuberculosis, blindness, as well as malnutrition, were their common inheritance.

They labored for stern taskmasters who rarely took pity on them. In England, apprenticeship and poor laws doomed these children to a slave-like relationship with their Master-Sweep. These masters, who never did any of the cleaning work, were the ones who dressed themselves in the top hat and tails, purchased second-hand from undertakers, that came to symbolize their profession. The chimney sweeps themselves wore only rags.

The arrival of the 1900s and the increasing use of gas, oil and electricity, eventually made chimney sweeps as archaic as blacksmiths.

Though gone for more than a generation by the time souvenir postals became all the rage, chimney sweeps were featured on numerous cards. But only on New Year’s Day greetings, never on occupational sets. All sets of working people, such as Pictorial Stationery Company’s “Familiar Figures of London” (1901); C. W. Faullfner’s Series No. 564, “Cries of London,” and the French “Les Cris de Paris,” completely ignored the chimney sweep. Even Raphael Tuck and Sons Company’s many comic valentine sets of this era, depicting all sorts of working people and characters, bypassed them.

New Year’s Day postcards with illustrations of chimney sweeps were all made in Europe – mostly England, Germany, Hungary and Austria, by about a dozen different printing houses. They were captioned “Happy New Year” in a fo eign language. Large numbers, though, were imported to the United States for sale to first and second generation immigrants from these countries. German-Americans, especially, were attracted to such cards for exchanging with each other.

New Year’s Day postcards with illustrations of chimney sweeps were all made in Europe – mostly England, Germany, Hungary and Austria, by about a dozen different printing houses. They were captioned “Happy New Year” in a fo eign language. Large numbers, though, were imported to the United States for sale to first and second generation immigrants from these countries. German-Americans, especially, were attracted to such cards for exchanging with each other.

Scenes usually depicted young children; and, infrequently, an adult. Most are shown only with the ladders and brushes of their trade; off and on/ though other paraphernalia are portrayed. Various traditional New Year’s Day motifs, such as pigs, flowers or sacks of money, often crept in.

Generally speaking, production of chimney sweep themed greeting postcards for the holiday stopped in 1914, when World War I engulfed Europe. After the 1918 Armistice, the old days and the old ways were forgotten as the world rushed toward the modern era.

So as we sweep away the old year and prepare to welcome in the new, let us give a quick thought to the little lads of yore who, with their cleaning brushes and ladders, decorated so many New Year’s Day greeting postcards a century and more ago.

Follow Us