Compiled by Peggy DeStefano

Compiled by Peggy DeStefano When my husband Jon was a new teacher in Denver Public Schools, we had the pleasure to meet Omar Blair. It was obvious that there was something special about this man. At the time we met him he was on the Denver School Board. Everyone soon learned that he had a history that couldn’t be ignored. He was, after all, a Tuskegee Airman when he was a younger man.

Here is what was said of Omar Blair when he passed away in 2004:

Omar Blair was born in Texas in 1918, and attended high school in Albuquerque where, as one of six black students, he was not allowed to sit with the other students at graduation. But in 1979 he was named the most distinguished graduate of the same school! Growing up he wanted to become a pilot, however at that time the United States Army Air Corps was not accepting Black candidates for pilot training. In 1940 he enrolled at UCLA, and during his second year there the USAAC relaxed its colored restriction, and after passing the required tests he was sent to Tuskegee, a small college town in Alabama to become one of the first Black pilots. Whereas white cadets progressed through their training at different bases, the black pilots did all their training (Basic, Primary, and Advanced) at Tuskegee at different fields around the town, and they became known as “the Tuskegee Airmen.”

Blair proceeded with this 332nd Fighter Group to Italy, where they entered combat, originally flying P-40 airplanes, but later the most advanced US fighter, the P-51 Mustang. Their record for escorting bombers to the war zone was exemplary. They claimed that no bomber they were escorting was ever shot down. As well Blair became known as “the Great Train Robber.” When their base was running short of fuel he organized a convoy to hijack a train bound for another base and take the fuel tanks it was transporting to his base! Following the war he spent some time in Albuquerque, but moved to Denver in 1951 where until 1969 he worked at The Rocky Mountain Arsenal, while remaining in the Air Force Reserve from which he retired in 1985 as a Major. In 1970 he moved to Lowry Air Force Base as the Equal Opportunity Officer, and while there in 1973 he ran for and was elected to the Denver Board of Education, where he served until his retirement in 1985. In 1975 he became vice president of the Board, and two years later he became its first Black president, serving until 1981. It was during this period that Denver was required by a US Supreme Court decision of 1973 to integrate its schools and begin busing of students to achieve this, although several of the buses were bombed during this time.

Blair also served as Commissioner of the Denver Urban Renewal Authority during the time that they initiated the Sixteenth Street Mall. In 1984 he received an Honorary Doctorate from Metro State College as a “Doctor of Public Service” for his many years of service to education. In 2003 the Blair-Caldwell African American Library at 2401 Welton Street was dedicated to him and Elvin Caldwell, the first Black member of the Denver City Council, and a manager of the Denver Department of Safety. In 2004 the Edison Charter School in Green Valley Ranch was renamed the Omar D. Blair Charter School, also honoring Blair’s work in education.

Blair also served as Commissioner of the Denver Urban Renewal Authority during the time that they initiated the Sixteenth Street Mall. In 1984 he received an Honorary Doctorate from Metro State College as a “Doctor of Public Service” for his many years of service to education. In 2003 the Blair-Caldwell African American Library at 2401 Welton Street was dedicated to him and Elvin Caldwell, the first Black member of the Denver City Council, and a manager of the Denver Department of Safety. In 2004 the Edison Charter School in Green Valley Ranch was renamed the Omar D. Blair Charter School, also honoring Blair’s work in education. Omar Blair died in 2004, and is buried near the center of Block 121 of Fairmount Cemetery. The information in the obituary was provided by Tom Morton.

It didn’t register to me what exactly being a Tuskegee Airman meant until this past month when we had another Tuskegee Airman share with my chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution what a Tuskegee Airman was and what they had to go through to become the famous flyers that they were.

This is an excerpt from his presentation:

When most of us think about “Top Gun,” we usually associate it with Tom Cruise’s character during the ’80s movie showcasing the Navy’s F-14 Tomcat exploits and over-the-top maneuvers. But in reality, it was a Tuskegee Airmen who took part and won the military’s first “Top Gun” style competition.

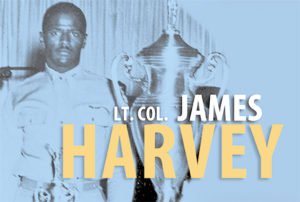

Born in Montclair, N.J., on July 13, 1923, to a poor but proud family, James H. Harvey III served more than 20 years in the military and would go on to become of a member of the famed Tuskegee Airmen and the first African-American pilot to fly combat missions over Korean airspace.

Harvey is also one of two surviving Tuskegee Airmen who won the Air Force’s inaugural weapons meet in 1949. The other survivor is Master Sgt. Buford Johnson.

Harvey is also one of two surviving Tuskegee Airmen who won the Air Force’s inaugural weapons meet in 1949. The other survivor is Master Sgt. Buford Johnson. After being denied an enlistment in the Army Air Corps for cadet pilot training, Harvey was drafted into the Army in 1943 and boarded a train for Fort Meade, Md., where he took his physical and written examinations. Based on his written examination score, he was assigned to the Army Air Corps Engineers to be a bulldozer operator to clear areas for airfields.

“I decided this was not for me, so I applied for cadet training again,” he wrote on his website. “This time, I was accepted and reported to Bolling Field, D.C., for my written test and physical examination, which I passed with flying colors. There were 10 of us taking the examination, nine Whites and myself, and only I and one White passed the examination to attend Pilot Training School.”

After passing his examination, he was accepted to attend pilot training at Tuskegee Army Air Field. While there, Harvey said he spent his primary training by alternating half his day learning to fly aircraft and the other half at the Tuskegee Institute where he and other cadets had classes in math; English; Morse Code; aircraft, ship submarine identification; and navigation.

After he graduated his primary training, he said he went on to advance training on the AT-6 aircraft until he graduated as a second lieutenant Oct. 16, 1944.

Harvey’s first duty assignment was the 99th Fighter Squadron at Godman Field, Ky. Four years later in 1949, Harvey competed in the first USAF Weapons Meet at Las Vegas Air Force Base, Nev. As a first lieutenant, he, along with Capt. Alva Temple and 1st Lt. Harry Stewart, represented the 332nd Fighter Group Weapons Team where they won the competition flying their P-47N Thunderbolts. However, their victory wasn’t officially recognized until April 1995, he said.

Later that year, he was assigned to Misawa Air Base, Japan, where he served as an F-80 Shooting Star fighter pilot. Harvey would retire from the Air Force as a lieutenant colonel May 31, 1965.

On August 6, 2011, Harvey received the Noel F. Parrish Award — the Tuskegee Airmen’s highest honor at the Tuskegee Airmen 40th National Convention. This award recognizes outstanding endeavors to enhance access to knowledge, skills, and opportunities.

Harvey also shared some of the behind-the-scenes situations that made training to be a pilot in Tuskegee presented with many more indignities than you can imagine. They were told that they really shouldn’t leave their base because it was a time in American history that a black man could be abducted, castrated, lynched and burned. The airmen decided it would be better to stay on campus.

It is important to note that at the time African-American pilots trained at Tuskegee, the military was still completely segregated, which means the pilots’ planes were serviced by African-American mechanics and other specialists. Armament specialists trained at Lowry Field in Colorado, radio specialists at Scott Field, Illinois, and mechanics at Chanute Army Air Field in Illinois.

An initial part of the Tuskegee experience was getting hazed by upperclassmen, a tradition brought over from the military academies and four national Black fraternities where many cadets had gone to school before enlisting in the Army Air Corps. Cadets were forced to “eat a square meal”: they were only allowed to sit on one corner of their dining room chair, made to sit perfectly straight, and bring their forks from their plates to their mouths at a perfect right angle, without moving their heads. If food was dribbled, the cadet had to stand up and scream the humiliating phrase, “I am a sloppy dummy.”

Pre-flight cadets were also awoken in the middle of the night, ordered to put on their rubberized ponchos and gas masks, and made to do various physical drills all night — while still being expected to do their full physical training regimen in the morning, which began at 6 a.m., as well as class all afternoon.

In addition to fighting for their country, the Tuskegee pilots knew that the future of African-American pilots in the military rested on their performance, quite a heavy burden for 18-year-olds. Though many commanding officers did not want to employ Tuskegee fighters, Colonel Davis, (Air Force’s first African American general) a brilliant military strategist and lifelong military man, fought successfully for their chance to display their skills. The rest is history.

During the course of the war, 66 Tuskegee pilots were killed in combat, and 32 pilots were shot down and became prisoners of war. The Tuskegee pilots shot down 409 German aircraft, destroyed 950 units of ground transportation and sank a destroyer with machine guns alone — a unique accomplishment. However, their most distinctive achievement was that not one friendly bomber was lost to enemy aircraft during 2000 escort missions. No other fighter group with nearly as many missions can make the same claim. Reflecting their superior performance, they were called “Black Birdmen” by the Germans, and given the nickname of “Black Redtail Angels” by the Americans (because of the vivid red markings on their aircraft tails).

“The character, courage and commitment of the Tuskegee Airmen paved the way for their military comrades of every hue and color, race and creed to serve their Nation in combat side by side. Their selfless sacrifices have taught each new generation of Americans the true meaning of the American spirit — Unity, Resolve and Freedom.” — Charles S. Abell, Assistant Secretary of Defense

The “Tuskegee Experiment” was expected to fail. However, not only was the program a milestone in training African-Americans as military pilots, but the Tuskegee Airmen went on to succeed with flying colors. Tuskegee pilots garnered some of the most envied military records in history, and more importantly advanced the American Civil Rights Movement by setting the precedent that would force the American military to begin to fully integrate in 1948 — more than a decade before Martin Luther King Jr. marched on Washington.

The Tuskegee program also forged a group of men who would earn advanced degrees and make notable achievements in the fields of law, social policy, politics, medicine, education, and finance. Surprisingly, aviation was not on this list, as private aviation industries were closed at the time to African-Americans.

That the 926 service members who graduated from Tuskegee succeeded at a time when racist attitudes were officially sanctioned in the military is a testament to the men’s extraordinary determination to succeed as pilots, which by its nature is one of the most academically and psychologically challenging areas of military service.

Thank you, Major Omar Blair and Lt. Col. James H. Harvey III. I feel so lucky and honored to have crossed your paths.

Follow Us